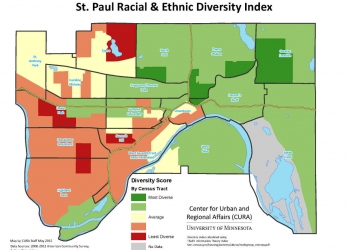

John Vaughn has thought for years that the east side of St. Paul has not received as much funding as other parts of the city. “Anecdotally, I’ve seen the East Side has lost out on city funding to other neighborhoods,” said Vaughn recently. “Having the City Academy project funding be so severely cut pushed me to organize around finding some hard evidence of this.”

In 2015 Vaughn, who is the executive director of the East Side Neighborhood Development Center (ESNDC), had put together an application to St. Paul’s Capital Improvement Budget (CIB) program for the rehabilitation of the rapidly deteriorating City Academy, the nation’s first charter school. The combination school and rec center serves mostly low-income students of color living on St. Paul’s east side. Vaughn had organized students to show up to committee meetings, gone through presentations, and finally secured what looked like a favorable result from the citizen-led CIB committee, which awarded the rehab project a few million dollars. But then the recommendations went to the Mayor’s office, and the few millions of dollars in funding for a completely rehabbed City Academy turned into $500,000–barely enough for deferred maintenance.

Again, Vaughn was frustrated, but not surprised. “The East Side has long suspected that it has not been getting its fair share of resources” said Vaughn. “We intend to continue to research and make public these disparities.” The rehashing of the CIB budget that left City Academy out in the cold was a final impetus to get a basic question answered: when you look at the numbers, do some neighborhoods really get more Capital Improvement Budget funds than others?

To answer this question, the ESNDC partnered with Dayton’s Bluff Neighborhood Housing Services and the Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers to develop a research proposal. “We gathered community organizations together that had seen this themselves and had an interest in seeing what spending actually looks like from a geographic perspective,” Vaughn explained. “So once we had a proposal we approached the Community-Based Research Program at CURA.” The Kris Nelson Community-Based Research Program at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) received a proposal to conduct an analysis of the St. Paul Capital Improvement Budget Process. They wanted to learn if what they had anecdotally seen in their communities was borne out by the data. Which neighborhoods were getting the most CIB spending? How did the spending look when compared to property tax data? Was the CIB process equitable? Were the results fair? These and other questions were the starting place for this research project.

The project was accepted by CURA. Jeff Matson, the head of CURA’s Community GIS program, took on the initial stages of the project work. The first step in the analysis consisted of tracking down and analyzing CIB budget spending to determine if spending really was unequal across districts. The city of St. Paul publishes a complete Capital Improvement Budget every year, and this budget provides a breakdown that describes each individual CIB project, how much was spent on it, and which districts the projects impacted.

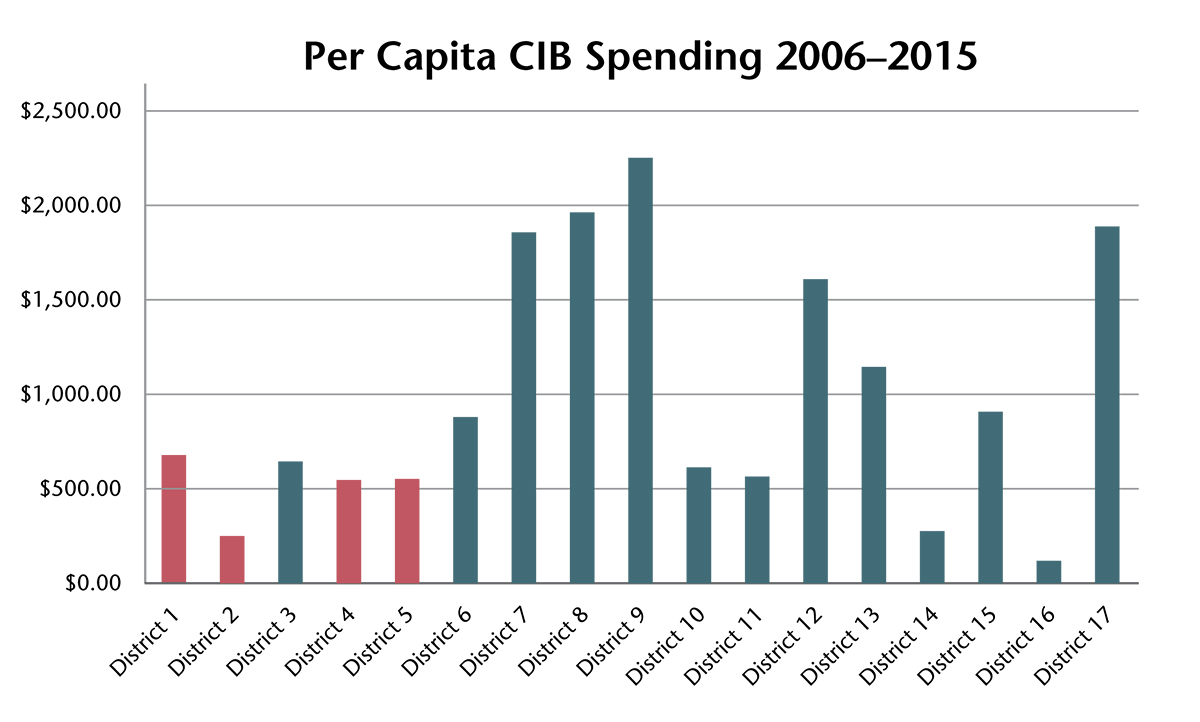

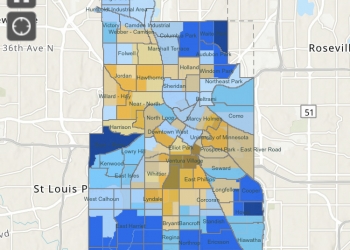

Matson and his team spent around 200 hours combing through the last 10 years of those published CIB budget files (from 2006 to 2015), entering the data and finally analyzing it by district. In the end, the backbone of the report emerged: a graph showing the last 10 years of per capita CIB spending across St. Paul’s 17 planning districts. These results showed the four planning districts that make up the east side of the city as receiving some of the lowest amounts of CIB spending.

With these surprising numbers on hand, CURA and ESNDC talked with each other about how to best go forward with creating a report. There were still outstanding questions to be answered. Simple questions, like, “Can there be another explanation for these surprising discrepancies?” And more complex questions, like, “What does an equitable CIB process look like?”

To answer some of these questions, the study was expanded. The expanded portion of the study was a qualitative analysis of the CIB process and the initial findings from the data analysis. Two student researchers worked under the direction of Ryan Allen, an Urban and Regional Planning professor at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, to conduct semi-structured interviews with a variety of CIB stakeholders. The interviews were voluntary and all names were withheld. Interviewees included CIB committee members, city officials, city staff, and elected officials. The interviews had two major purposes: to better understand the CIB process, and to receive feedback from CIB experts on the initial data analysis findings. For this portion of the project, institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained, which meant that all interview recordings and notes were withheld from ESNDC and any other entities.

Finally, a report was developed. The report provides an overview of the CIB process, summarizes the findings of the data analysis, and synthesizes the interview responses from the interview subjects. From this analysis it derives recommendations for potential alterations that could be made to the CIB program in order to make it more equitable.

Soon after the final report was published, local papers picked up on the story, thanks in large part to the advocacy of Vaughn and his community-based colleagues. The Star Tribune, Pioneer Press, and KSTP Channel 5 news ran stories on the surprising per-capita disparities outlined in the report. This prompted the City of St. Paul to issue rebuttal statements calling the report “misleading and incomplete,” and referring reporters to an analysis of its own. CURA explained its methodology (as it is explained in the report), and was not shown by either the Mayor’s office or the Office of Financial Services to have done anything incorrectly. A comparison of the City and CURA analyses can be found online at z.umn.edu/1d2i.

“If you look back,” Vaughn notes, “it is amazing how much great community and economic development work in Minneapolis and St. Paul was built on a CURA study.”

All this discussion about the fairness of CIB, considerations of equity, and the per-capita spending discrepancies across districts found in the CURA analysis, led the St. Paul City Council to pass a resolution to streamline the CIB process for 2018–19, gather community input, and ensure that future funding decisions would be in part dependent on geography, equity, and inclusion.

In the end, this report shows how the CURA Kris Nelson Community-Based Research Program can work with local community nonprofit partners to develop research project that lead to meaningful policy change in their communities.