We would like to acknowledge all the partners and community leaders that made this work possible, including: the Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative Action Committee (Desiree Clabon, Charletta Mosely, Chiquita Baptiste, Craig Kurzawski, Demetrius White, Amisha Harvey, Stephanie Moniz, Kaitlin Fischer, Bobbi Lynn Credit, Shannon Harrison, Tyra Thomas, Halie Gudmonson); the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA); People Serving People; the People Serving People Guest Advisory Council; Research in Action (RIA); Hennepin County; the interviewees from The Illusion of Choice: Evictions and Profit in North Minneapolis report; Drexel University Building Wealth and Health Network Program; and the Pohlad Foundation.

Introduction

“They were paying two, three thousand dollars a month for the shelter, but was taking more money than that from me. If they woulda just let us save that money for one month, we woulda been outta there the first month.” (Black, male, 28)

“So then how do you get ahead? I mean how do you then say, ‘Well you know, I don’t want to be here forever.’ You know what I mean? And I learned that as a result of the situation, too. I said ‘Wow.’ And then they wonder why folks become dependent and are there forever.” (Black, female, 70)

In the 2019 report The Illusion of Choice: Evictions and Profit in North Minneapolis, Dr. Brittany Lewis and her team at the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) explored the landlord-tenant power dynamic in North Minneapolis. Findings suggested that tenants of color were often subject to the economic imperatives set forth by distressed property investors, many of whom were not compelled to provide safe, affordable, quality housing. This power imbalance and the tactics used by landlords to mitigate risk and exercise power resulted in tenants, often single Black mothers, trapped in a system where they were living one crisis away from an eviction. As Dr. Lewis and her team began to interview individuals that had become homeless as a result of an eviction, they discovered that many were choosing to sleep in their cars to avoid paying to stay in local Hennepin County shelters. Because of this discovery, one of the three policy recommendations that the Illusion of Choice report made was to end the county’s policy on self-pay at shelters, enabling shelters to develop and implement asset-building and empowerment programs for shelter guests.

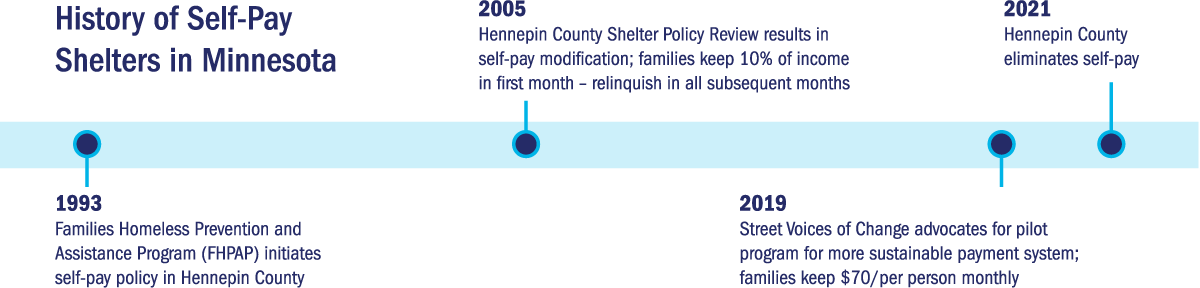

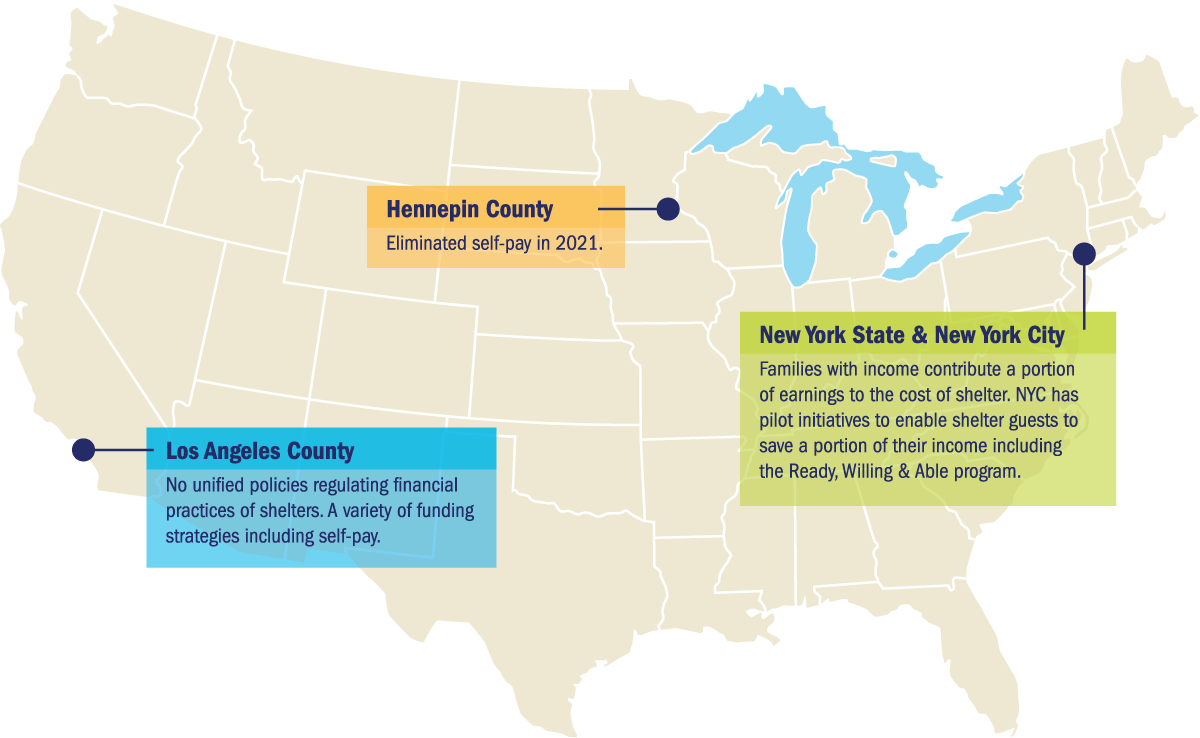

Since 1993, Minnesota has enacted multiple iterations of pay-to-stay models into statewide shelter policy. While the self-pay model is not widely adopted across the nation, it is an approach that has been discussed and practiced in regions where issues of housing instability are most serious, including Los Angeles County and New York State. This model proclaims “financial empowerment” as a key tenet, seeking to inspire financial responsibility among shelter guests and to disincentivize prolonged stays in shelters. Despite the stated goals of self-pay shelters, the pay-to-stay model has faced opposition, suggesting it exacerbates economic instability and diminishes opportunities for sustainable permanent housing.

Following the release of the evictions report, it became clear that there was a significant but unconnected group of advocates, funders, shelter leaders and county leaders interested in reimagining Hennepin County’s self-pay policy. The Pohlad Foundation, a funder of the evictions report, was seeking actionable steps to invest in and opportunities to fund innovative strategies at sustainably disrupting poverty. People Serving People, an emergency shelter in Hennepin County, had been seeking opportunities to challenge self-pay but were contractually obligated to enforce the policy. Representatives from Hennepin County had worked with Dr. Lewis and other housing advocates to redesign the emergency assistance process and were interested in furthering housing equity in the county. In January of 2020, this coalition, funded by the Pohlad Foundation, including staff from People Serving People, Research in Action (RIA), researchers at CURA and employees from the Hennepin County Economic Supports formed the Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative (FFEC) to explore an alternative approach to the self-pay policy in Hennepin County.

The collaborative’s goals were to:

- ensure that homelessness is rare, brief, and non-recurring;

- identify strategies to build families’ financial power;

- create financial sustainability for families and the county; and

- address racial disparities in the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous families experiencing homelessness.

By employing participatory action research strategies, FFEC engaged current and former shelter guests to co-develop an alternative to the self-pay model.

The first part of this paper outlines the process this coalition undertook to co-develop the Families for Finance (FFF) Program, a financial empowerment model informed by needs and experiences articulated by shelter guests.

The collaborative model development process revealed that:

- residents desired tangible financial support and autonomy,

- many shelter guests experienced ‘financial trauma’ as a result of prolonged economic insecurity, and

- participants desired opportunities for communal learning and peer accountability.

The second part of this paper discusses the challenges of building and implementing an innovative pilot program under the constraints of COVID-19 and a rapidly changing policy landscape, including the elimination of the self-pay policy mid-way through implementation of the pilot program. Finally, this paper seeks to identify lessons learned and future opportunities for FFF or similar financial empowerment and asset-building models.

Background

Homelessness has been a persistent and growing social issue in the United States since the 1980s. In 2018, a total of 552,830 people experienced homelessness on a single night in the United States and about 33 percent of these individuals were part of families with children. Despite this troubling figure, the National Alliance to End Homelessness’ report indicates homelessness is decreasing; from 2007 to 2018 there was a national decline in homelessness of 15 percent including 38 states that observed a reduction to the number of people experiencing homelessness.[2][1]

During this same time period, however, Minnesota’s homeless population grew dramatically. According to the 2018 statewide survey conducted by Wilder Research, the homeless population has continuously increased in Minnesota over the past three decades and reached a peak in 2018. Among the 10,233 Minnesota residents experiencing homelessness, the report suggests that nearly 26 percent were not in a formal shelter. In 2015, 45 percent of homeless adults were on a waiting list for subsidized housing, with an average wait time of 14 months. Hennepin County accounts for 40 percent of the state’s homeless population and over the past decade the homeless population living outside of a formal shelter rose by 93 percent in the Twin Cities metro-area, driven primarily by single adults. Families experiencing housing instability actually decreased in Hennepin County at this time. The stark realities of homelessness became publicly unavoidable with the installation of the Hiawatha homeless encampment, named by those encamped there as “The Wall of Forgotten Natives” in 2018. The Wall of Forgotten Natives became the largest homeless encampment in the state with more than 300 tents, and primarily comprised of homeless individuals, stretching along the west side of the avenue.[5][4][3]

Evolution of Minnesota Self-Pay Policy Response to Homelessness

Prior to this state of emergency, state and local officials sought a number of policy solutions to address the needs of a growing homeless population, including requiring shelter guests to pay a portion of their shelter stay.

1993 Family Homeless Prevention and Assistance Program (FHPAP)

In 1993, the Minnesota Family Homeless Prevention and Assistance Program (FHPAP) was established by the Minnesota Legislature to address the growing demands for emergency assistance and shelter. FHPAP provides case management and financial assistance to individuals and families in order to prevent and solve homelessness. FHPAP funds are administered by Minnesota Housing and are awarded to grantees through a competitive RFP process. Alongside the FHPAP initiative, several concurrent efforts were implemented in 1993 seeking to avoid massive turn-aways of people experiencing homelessness, including maximizing shelter overflow capacity, targeting chronic shelter-user single adults for more intensive services and more accountability, and preventing or reducing the use of shelters by homeless families..Based on these strategies, a recommended policy document entitled, Plan to Meet Emergency Shelter Needs in Hennepin County, was proposed in 1994 claiming that:[7][6]

“persons who have demonstrated a pattern of homelessness due to the inability to manage income should be aggressively assisted and expected to achieve housing stability” (p. 3).

Therefore,

“All shelter clients with representative payee accounts managed by Hennepin County should be charged for shelter if they have sufficient funds” (p. 5).

This document and the introduction of the “pay-to-stay” provision became the foundation of Hennepin County shelter policy.

2005 Updated Hennepin County Shelter Policy

In early 2004, Hennepin County staff worked with the Community Advisory Board on Homelessness to bring Hennepin County’s emergency shelter policy up-to-date. The Hennepin County Shelter Policy Review was completed through the collaborative effort in late 2004. In February 2005, the review was presented to the Hennepin County Board and the updated Hennepin County Shelter Policy was released in November. According to the policy, Hennepin County would begin providing emergency shelter for families and disabled single adults. Distinct from the overnight shelter beds or safe waiting services provided for single adults, these would be 24-hour emergency shelters and would provide three meals a day. However, the policy stipulated that while in shelter families could only keep ten percent of their total income for basic needs in their first full month and must relinquish all available personal resources in every subsequent month until they moved to permanent housing. Only after these conditions were met, could the county assume shelter payments.

In addition to the support provided by the shelter, there are several social assistance programs that support homeless families’ basic needs while staying in shelters. These programs include the Supplemental Security Income (SSI), the Diversionary Work Program (DWP), Retirement, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (RSDI) and the Hennepin County Emergency General Assistance Program (EGA).

2019 The Self-Pay Program

Community advocates including Street Voices of Change (SVoC), an organization of individuals who have current or past experiences with homelessness, sought to transform the self-pay policy in order to allow shelter guests to maintain a portion of their income during their stay in shelter. Observing the social push for change from the community and SVoC, Hennepin County realized the need to reform the payment model. The county government partnered with the Salvation Army-Harbor Light Center (HLC), a county-contracted shelter, to implement a more sustainable payment system for sheltering families; this program mirrored the Diversionary Work Program, which allows for $70 per family member per month for personal needs. Starting in 2017, Harbor Light Center began implementing this modified self-pay program in which individuals were allowed to keep $70 per person per month until they moved into permanent housing. The self-pay program implemented at HLC inspired the development of a new self-pay policy in 2019 to which all other contracted shelters in Hennepin County were required to adhere.

Between July 1, 2019 and September 30, 2019, the Hennepin County Shelter Team piloted a new policy seeking to afford families more control over their resources during their time in shelter. The pilot provided that families were allowed to retain $70 per person per month out of their income for additional personal needs (e.g., baby and child needs, cell phone plans, gas, personal hygiene needs, storage, transportation, etc.) beginning the first full month in the shelter. All families who were eligible for shelter were automatically enrolled in this pilot regardless of income source and family size. All contracted shelters in Hennepin County were included. The difference between shelter cost and self-pay amounts continued to be covered by the Consolidated Fund.[8]

The Hennepin County Shelter Team evaluated the self-pay pilot in October 2019. A set of pre- and post- personal needs surveys were administered to families in shelter to inquire about how individuals spent the $70 per person per month while in shelter. In total, 69 pre-survey responses and 23 post-survey responses were collected. The results demonstrated that increasing the amount of money that families could keep for their personal needs expanded their available choices and increased their sense of empowerment. The two main expenditures that families reported were cell phone plans and purchases associated with personal hygiene. Other categories included application fees, infant and child needs, food, storage, transportation, and gas. In the pre-survey, 26 percent of participants indicated that they intended to save some of the money;however, the post-survey indicated that most of their funds were spent on daily personal and family needs, revealing that only four percent of respondents were ultimately able to save. Only 17 percent of participants reported spending money on interview costs; otherwise there were no other noted expenditures related to personal or family financial management and improvement.

One of the goals of the self-pay pilot was to keep shelter “use rare, brief, and non-recurring.” The evaluation team tracked the number of families, mean length of stay (days), the median length of stay (days), and the number of recidivist households between April 2019 and December 2019. The recidivism rate in December 2019 was 44 percent (61 out of 138).[10][9]

The self-pay pilot was met with both support and opposition. Proponents of the policy suggested that contributing to the cost of shelter stay incentivized families to prioritize job acquisition and to vacate the shelter expeditiously. Advocates of this policy pointed to the fact that shelters with free stay protocols usually have an average stay of several months or even years, while the typical stay of a self-pay shelter is a bit over a month. Furthermore, champions of the policy suggest that the $70 per person per month empowers families to make decisions about how to allocate their resources and how to meet their needs.[12][11]

Those in opposition to the self-pay pilot argued that although the pilot was a step forward, it remained difficult for families to abdicate control of their own income. People Serving People’s staff, for example, shared that the self-pay policy is the number one shelter policy with which residents express frustration. Some shelter residents suggested that while there may be benefits to the self-pay policy, the structure and required contribution was onerous. One participant made the point,

“The self-pay policy is not the problem, it’s the amount of it that’s an issue. Life is expensive and kids are expensive especially when they grow, so I believe that self-pay policy is not all bad, it just needs some modification” Black Female, Late 30s, Former Shelter Resident.

In some community meetings, some social service providers suggested that the self-pay pilot was a barrier to families successfully exiting shelter. [13]

Shelters in Hennepin County

The self-pay program has been implemented differently by shelters across Hennepin County. To better understand how the self-pay program is applied in local shelters, how it influences shelter operation, and how it influences the financial capability of shelter guests, we researched Hennepin County-based shelters and reached out to administrative employees to clarify their practices and experiences.The table below highlights the variation across shelters in terms of funding mechanisms and financial empowerment programming. This information was gathered by reviewing program websites and discussions with shelter employees.

FFEC sought to utilize this local shelter comparison to inform the improvement of the current self-pay policy or to consider alternative options.

| Salvation Army– Minneapolis Harbor Light Center (HLC)[14] | People Serving People | Mary’s Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost to Residents | Self-Pay | Self-Pay | Free |

| Shelter Population | Single Adults | Homeless Families (i.e., father with kids, mother with kids, couple with kids, or single pregnant people) | Homeless families with children |

| Program Model | HLC was created to support people with disabilities living in traditional group residential housing. It was not meant to be funding for short-term emergency shelter. | Emergency shelter, basic amenities, and engagement services to support parents’ and childrens’ development, including case management and on-site medical clinic | Emergency shelter, basic amenities, case management, on-site medical and dental clinics, legal resources, county welfare assistance, daycare services, and public-school liaisons |

| Financial Resources | Housing Support funding and self-pay protocol (individuals can retain 70 dollars per person per month while staying at the shelter) | TANF/MFIP Consolidated Fund, self-pay protocol, and philanthropic fundraising[15] | Private donations from grant foundations, corporations, and the general public |

| Financial Empowerment Services | HLC does not provide financial literacy or money management programs for clients yet. | Financial fitness curriculum is called “Money on My Mind.” The goal of this program is to educate families on the cornerstones of financial literacy. Monetary incentives encourage program participation and saving. | Family Advocate caseworkers assist families to budget and create monthly savings goals, as well as guiding them to appropriate resources/services, and refer families for further financial education and management. Internal Job Seeker Program, where trained volunteers come on-site to provide clients with one-on-one assistance with resume building/online job search/interviewing skills, etc. |

| Outcomes and Impact | On average, HLC serves 180 people per night | In 2022, PSP had an average of 83 families/night; with capacity for up to 99 families. | On average, Mary’s Place serves 100 families per night |

National Examples of Self-Pay Models

The CURA team sought literature on self-pay/pay-to-stay shelter policies and practices outside of Hennepin County to provide information to the collaborative tasked with forming an alternative financial empowerment model. However, we quickly learned that there were few academic articles published on this critical issue. Of the 284 articles we identified, 229 were newspaper articles. The 36 peer-reviewed articles contained “shelter” in the title and “pay” in any field of the article, but none of them had a focus on the self-pay policy development process/discussion or specific case studies around this topic.Therefore, we turned to Google and learned from national and local news outlets (i.e., Los Angeles Times, New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, U.S. News, Star Tribune) and opinion pieces on blogs. These sources led us to specific areas, shelters, organizations, and policymakers that have been involved in the discussion and actions for many years. Our strategy was then to divide our time between examining online media sources and engaging in outreach with relevant stakeholders. Based on this outreach, we discovered the following information about self-pay policies in New York City/New York State and Los Angeles County.

New York City (NYC)/New York State (NYS)

The steady decline in housing affordability was a major reason that low- and middle-income families were pushed into homelessness in New York City. Between 2000 and 2014, the median New York City rent increased by 19 percent and household income decreased by six percent. Since 2008, there has been a steady increase in the number of homeless single adults in New York City (NYC). In 2019, NYC had more than 60,000 homeless people in shelters each night, including nearly 18,000 single adults. In 2019, 70 percent of shelter guests were people in families, and the majority of the families in shelters are headed by single mothers. On any given night, there are approximately 15,000 children aged from four to 17 experiencing homelessness and residing in NYC Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters every single year according to DHS2.9 Unlike other states and areas, NYC has far more working homeless families in part because of the high cost of housing. A study conducted by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition showed that in NYC, 45 percent of homeless single adults and 38 percent of homeless adults in families earn wages while being homeless, which ultimately was a factor used to champion the self-pay shelter policy in this area.[18][17][16]

Since 1997, New York State (NYS) and New York City have required that the financing for family homeless shelters align with public assistance policies so that those families with income would contribute a portion of earnings to the cost of shelter. The methodology for determining the amount families contribute was based on how cash grants are pro-rated to account for other household income. Although the self-pay policy was implemented throughout NYS, the new requirement faced extreme opposition from the public and advocates of homeless communities in NYC.

Because of this strong advocacy, the NYS legislature passed a law in 2010 that exempted NYC from the income contribution requirement, but required NYC to develop an alternative pilot program that would allow shelter guests to save a portion of their income instead of paying toward the cost of the program. This innovation also faced opposition, in part because shelter guests were normally living under the poverty line and advocates suggested that the mandatory savings would likely make residents remain in shelter longer with fewer financial resources. Between 2010 and 2019 NYC piloted various voluntary and mandatory savings programs.

An alternative program, financed by the Doe Fund, a nonprofit social enterprise in NYC, offers an innovative model for financial empowerment. The Ready, Willing & Able program offers free transitional housing for adult males; services also include vocational training and paid off-site work. Participants are required to deposit a portion of their weekly earned income into a savings account that is matched by the Doe Fund at the end of the year. While not an emergency shelter, it provides a holistic alternative to supporting economic stability.

Los Angeles County

The State of California has about 134,000 homeless people, approximately 24 percent of the nation’s total. In 2019, there were 56,257 homeless people in Los Angeles (LA) County, an increase of about 40 percent since 2014. As of the 2019 census, Skid Row, a neighborhood in downtown Los Angeles, has accounted for about 2,783 homeless people, making it one of the most condensed homeless population areas in the United States. The homeless population count in the Service Planning Area (SPA) 4, where Skid Row is located, was 16,436 in 2019, 12,281 unsheltered (75%) and 4,155 sheltered (25%), which is the highest percentage of unsheltered individuals in the United States.[20][19]

In LA County, there are no unified local policies that regulate the financial practices of shelters, and as a result, there are a variety of funding strategies, including pay-to-stay, utilized by local shelters. One shelter in Skid Row, Union Rescue Mission’s (URM) Gateway Project, employs a self-pay model. URM indicated that following the 2008 financial crisis, the drastic increase in homeless individuals resulted in significant financial turmoil for the shelter. URM reported that government contracts did not fully cover program expenses, and, therefore, they sought an alternative sustainability plan, in part by requiring residents to pay a fee for shelter.

The table below highlights the funding structure and programming provided by the four long-standing shelters in Skid Row.

| Midnight Mission | Los Angeles Mission | Emmanuel Baptist Rescue Mission | Union Rescue Mission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | Free of cost | Free of cost | Free of cost | 300 pay-to-stay beds ($7/night) for single adults; free for families |

| Financial Resource | Donations (60%) Government Funding (40%) | Donations ( Individuals 70% Foundations 8% Businesses 17%) | Donations (100%) | Program fees and donations |

| Financial Empowerment Services | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Outcomes and Impact | (2019) 80% of clients moved to permanent housing; the average number of days between program-exit and re-entry is 121 days | (2018) 126,984 nights of shelter; 393,02 meals; 270 enrolled in the 12-month residential rehabilitation program; 3,347 had career guidance, 150 attended annual job fair | N/A | 250,000 people sheltered per year; 20% increase in long-term program; 100 of the Gateway project participants have secured permanent housing; reduced emergency and police calls |

Lessons for Hennepin County

The Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative (FFEC) utilized the Hennepin County shelter comparison, practices identified in LA, and the policy development processes in NYC as rich case studies to inform the development of an alternative to Hennepin County’s self-pay program.

Notably, the review of these pay-to-stay programs revealed that shelters that decided to charge clients such as Union Rescue Mission in LA and Harbor Light Center in Hennepin County, were often under financial pressures, attempting to make ends meet, especially during periods of economic tumult. Furthermore, although shelter clients’ financial literacy and capabilities are expected to improve while in shelter, few self-pay programs offered these services. Some programs provide general life skills programming aimed at improving academic and professional skill sets, others provide budgeting and financial counseling, but many programs have very limited, if any, financial education or support mechanisms built into their model. Finally, alternative approaches such as the Doe Fund’s Ready, Willing & Able program’s programmatic model present the possibility of engaging both the pay-for-stay idea and the goal of financial empowerment.

The FFEC presented these models in great detail to current and former shelter guests to consider what programmatic elements should be included in the Hennepin County alternative to the existing self-pay model.

Methods

Model Development

CURA utilized a participatory action research (PAR) approach informed by Research in Action (RIA) to develop an alternative financial empowerment model to the self-pay strategies employed in Hennepin County. Key to the PAR approach is researchers and participants working together to develop a shared understanding of a problem and co-creating solutions. In this case, CURA worked with nine current, returning, or former People Serving People (PSP) shelter guests to initiate the Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative (FFEC) Action Committee.

People Serving People (PSP), Hennepin County, and CURA supported recruitment and outreach efforts for this action committee, in part, by distributing an informational flyer and utilizing PSP’s existing database of past and current shelter guests. The solicitation flyer articulated that the Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative (FFEC) was exploring an alternative approach to the self-pay policy to reduce the burden for families experiencing homelessness toward stability. The flyer indicated the expectations of joining the action committee, including attending virtual meetings and sharing their housing experiences. Furthermore, the flyer indicated that there would be a $50.00 stipend provided after each meeting (refer to Appendix A for this flyer).

In order to participate in the action committee, participants had to either 1) submit a paper application to PSP, 2) submit an online application, or 3) submit a video answering the application questions (refer to Appendix B for the application questions). Prior to the first action committee meeting, the CURA team communicated with committee members to introduce the research team, provide an overview of the project, discuss key objectives, clarify roles and responsibilities of the committee, and communicate logistics regarding upcoming action committee sessions (refer to Appendix C for the intake script utilized by the outreach team). Furthermore, committee members were asked to complete a baseline survey in order to develop a shared understanding of key terms and topics for the working group (refer to Appendix D for baseline survey).

Between August 10, 2020 and October 26, 2020, CURA and PSP facilitated five sessions with the FFEC action committee to 1) build rapport and trust among action committee members, 2) come to a shared understanding of local and national self-pay policy approaches, and 3) develop an alternative empowerment program for PSP to pilot. CURA designed each action committee workshop using qualitative research methods with semi-structured scripts for data collection. These sessions resulted in the development of the Families for Finance (FFF) program.

| First Action Committee Meeting | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 10, 2020 |

| Goal(s)/ Activities |

|

| Action Committee Feedback and Key Quotes | The ability to have consistent, safe, affordable, and stable homes Understanding financial trauma as a precursor to financial literacy |

| Second Action Committee Meeting | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 24, 2020 |

| Goal(s)/ Activities |

|

| Action Committee Feedback and Key Quotes | “Instead of forcing homeless families to give shelters 100% of their income, (NONE of it goes into a savings account they can access once they move out by the way), a percentage of their income should be put into a savings account that could be used for apartment applications, first month’s rent and deposit” (Black Female, Middle Age, Previous Shelter Resident) “Doe Fund, where shelter guests are provided with paid off-site work, is better as it breaks the stigma that brown people are lazy and don’t work. Doe Fund also is better for women with children because it helps them learn a new skill and earn their own sources of income. (Black Female, Late 30s, Shelter Resident) |

| Third Action Committee Meeting | |

|---|---|

| Date | September 14, 2020 |

| Goal(s)/ Activities |

|

| Action Committee Feedback and Key Quotes | “The self-pay policy is not the problem, it’s the amount of it that’s an issue. Life is expensive and kids are expensive especially when they grow, so I believe that self-pay policy is not all bad, it just needs some modification” (Black Female, Late 30s, Former Shelter Resident) “Self-pay policies in the county, both the old and the new don’t help families move towards financial sufficiency, I was staying in a shelter back in 2011, and I had seven children, I used to pay USD 262.89 a night, I was only able to cover three nights and whatever was left was just enough to put money on my bus card and get back to work to do it all over again” (Black Female, Middle Age, Former Shelter Resident) |

| Fourth Action Committee Meeting | |

|---|---|

| Date | September 28, 2020 |

| Goal(s)/ Activities |

|

| Action Committee Feedback and Key Quotes | “Shelter families should be able to do their own calculations and make their own decisions (be offered different options and solutions) to how they wish to be empowered” (Black Male, Middle Age, Former Shelter Resident) |

| Fifth Action Committee Meeting | |

|---|---|

| Date | October 12, 2020 |

Goal(s)/ Activities

|

|

| Action Committee Feedback and Key Quotes | “Financial partner should be someone who has investment knowledge and has the ability to teach us what to do with our money, they should know about investment tools such as bonds and stocks” (Black Male, Middle Age, Former Shelter Resident) |

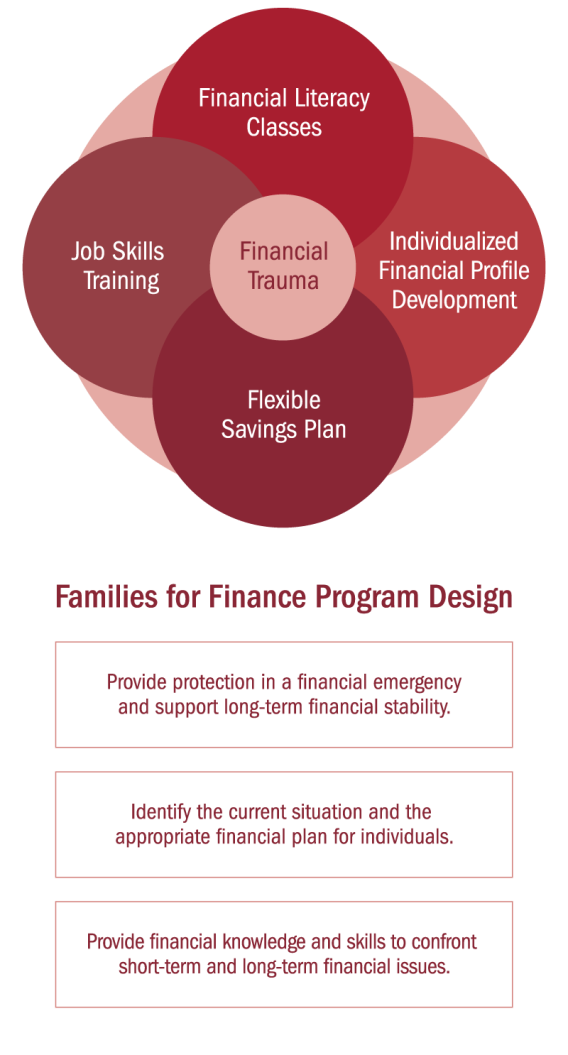

Families for Finance Program Description

The Families for Finance (FFF) program, designed by the FFEC action committee, aims to empower families living in shelters by not only increasing their financial literacy, but also by centering cultural awareness and trauma-informed care as program pillars. The FFF program includes financial literacy courses, financial profile development, peer mentorship (accountability partnership), and a savings plan for families. Individualization is a key principle within the program, in which families are given an opportunity to discuss their particular needs and create a plan unique to them.

Figure 1. Families for Finance Program Pillars

The specific objectives of the FFF program include:

- Financially empower families in shelter

- Reduce financial trauma that families experience

- Address cultural attitudes toward wealth and relationship with money

- Enable families to have control of their personal financial goals, responsibilities, decisions, strategies, and future

- Improve financial literacy

- Increase knowledge and ability to handle personal/family finances

- Enable families to improve financial outcomes through appropriate tools and financial plans

- Facilitate long-term success and stability

- Realize housing stability and/or home ownership

- Stay financially healthy, wealthy, and wise

- Create generational wealth

Key Program Features:

Day-by-Day Overview:

- Day 1:

- Families arrive at shelter

- Families automatically enroll in self-pay

- 15-day grace period begins

- Day 2 - Day 7:

- People begin to recover from mental/emotional/physical health issues using existing shelter resources

- Program Coordinator:

- Provides 1:1 counseling about self-pay and the alternative pilot program

- Conducts 1:1 assessment for financial trauma

- Day 7 - Day 10

- Program participants get an overview of the pilot program, initial assessments, and assignment of mentor/accountability partner

- Day 10-14

- Allow the family to go through the program features to understand how it could help them and hence make an informed decision.

- Talk to mentors, understand their experience

- Sit through financial literacy classes

- Learn more about savings account and matching feature

- Day 15

- The 15-day grace period ends and families select self-pay or alternative pilot

- the default is self-pay, families must opt into the FFF program

- The 15-day grace period ends and families select self-pay or alternative pilot

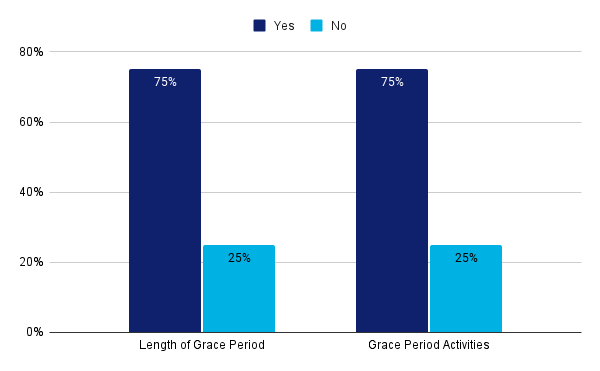

15-Day Grace Period: The action committee felt that a grace period was an important feature of the FFF model to allow program participants to eliminate the immediate pressure on families entering shelter. Furthermore, the action committee suggested that this gave families time to better understand the FFF program and make an informed decision about whether to participate.

Mentorship/Accountability Partnership: The program coordinator reaches out to program participants who could potentially serve as accountability partners for each other. The accountability partners will hold each other accountable in this program, supporting and encouraging each other.

Financial Literacy Classes: The financial literacy classes were designed to be conducted in a group setting, but were also adapted to a 1:1 model to accommodate for COVID-19. Prior to the financial literacy classes each participant engaged in an intake session. Then financial literacy classes included 1) Financial Empowerment, 2) Savings and Budgeting, 3) Credit and Debit, and 4) Banks.

| FFF Class Topics | FFF Class Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Intake Session | The purpose of the intake session is to explain the program’s structure and elements to the participants. Additionally to explain and go over forms for the PSP FFF Program with the client/research participant. |

| Financial Empowerment | Financial empowerment session was the first session of the four series of classes to be administered. This session focused on understanding the participants’ early experiences with money management, explaining financial trauma to them and understanding what their hopes and dreams are for the future and what they hope to achieve by participating in this program. The activities presented in this class include handouts with the different concepts to be covered in this class and showing participants videos about redlining and collective racism activities that they may be experiencing without their knowledge. This session introduces new concepts and definitions to the participants. |

| Savings & Budgeting | The second class of the program is focused on introducing techniques to the participants on saving and budgeting to help them maximize the value of their money. The first part of the session includes explaining the difference between “wants” and “needs” to the participants by giving them two different decks of cards with different wants and needs and explaining to the participants how they differ. The second activity is teaching the participants how to use spreadsheets for budgeting and managing their money. The third and final activity is providing the participants with a list of techniques on how to save money when shopping for their basic needs of food and clothing. |

| Credit & Debit | The third session is focused on giving the participants a better understanding of credit and debt, deconstructing some of the myths about credit, teaching the participants how to monitor and build credit scores for themselves and different types of debt and its related terminologies. The activities used in this session varied between identifying true and false statements, using sheets to solve different mathematical problems, and explaining new concepts to the participants. |

| Banks | The fourth and final session is focused on learning the difference between banks and credit unions, learning some of the myths about banks, teaching the participants how to open bank accounts and what questions to ask when they are doing so. Some of the activities in this session are mainly presenting the participants with information sheets about the difference between banks and credit unions and checking and savings accounts. This class session uses storytelling as a learning tool. Staff frequently discuss their own experiences with the topics discussed in this class. It is used as a supplemental learning tool to the packet of information provided to the participant. |

Savings Accounts: While not a part of the program initially envisioned by the FFEC Action Committee, PSP realized early in pilot implementation that supporting participants to set up savings accounts as a component of class was a straightforward strategy for improving participant savings and reducing fear or apprehension about applying for an account.

PSP partners with Prepare and Prosper to leverage the Financial Access in Reach (FAIR) initiative, which seeks to help low- to moderate-income people seeking an affordable banking solution. The FAIR initiative was built, in part, upon the input of more than 150 financially underserved consumers who participated in listening sessions. The initiative is led by a cross-sector leadership team representing the communities it serves.[21]

The FAIR initiative offers

- Checking accounts with no account overdraft fees or monthly minimum balance requirement

- Savings accounts with no monthly minimum balance requirement or monthly fees

- Credit builder loan: A loan deposited and saved into a CD. On-time payments to unlock the CD can help build credit.

Model Execution

A crucial aspect of the Families for Finance program was to identify the right financial partner to deliver the financial literacy classes to the participants. The research team at CURA, with help from representatives from PSP and the participants from the action committee, developed the Request for Proposal (RFP) (refer to Appendix F for the RFP). Some of the main requirements for the financial partner were that they have previous experience working with families to identify their own financial traumas and to co-develop an individualized plan and ability to facilitate the financial literacy class.

The first RFP was sent out in November 2020 and was posted for 30 days. The RFP was shared on several different platforms, such as PSP and CURA websites; however, only one proposal was received. After meetings and negotiations with the sole applicant, the FFEC committee decided not to proceed with the candidate as they were deemed unfit due to their lack of experience and the committee had concerns about their ability to run the program. The research team posted and circulated the RFP three additional times without finding an applicant that aligned with the identified program needs. After the fourth failed attempt, the Family Financial Empowerment Collaborative (CURA, PSP, Hennepin County) discussed whether an internal staff member from People Serving People could instead be trained to take on the role proposed in the RFP.

In the summer of 2021, the research team finally identified a qualified financial partner, “The Building Health and Wealth Network” (The Network). The Network is located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was established through a partnership with the “Center for Hunger Free Communities” at Drexel University. The Network is a trauma-informed, healing-centered financial literacy program that combines emotional and peer support to promote self-efficacy and resilience in traditionally under-resourced communities. In July 2021, The Network was finally hired as the financial partner for this project. In this role, The Network acted as a consultant to People Serving People staff responsible for ultimately implementing the financial empowerment model.

PSP staff participated in 11 hours of training with two Network coaches on the following topics:

- Individual trauma and healing centered engagement

- Collective trauma and healing centered engagement

- Sanctuary Model: Community Meeting and SELF Check-in

- Facilitation

- Coaching

- One-on-ones

- Coach Identity: Power, privilege, intersectionality

- Best Practices

- Financial Healing

The PSP staff observed and participated in two class sessions facilitated by The Network to gain context and understanding on how to create and facilitate a healing space in a financial setting. The Network also provided ongoing coaching to PSP in the form of one-hour weekly meetings for two months as PSP staff began working with clients.

Model Evaluation

During the pilot period, this evaluation focused on the output and short-term outcomes generated from program input and activities. The long-term successes were tracked in an extended timeframe which was not addressed during this current evaluation. The key evaluation questions were grouped into three categories:

- Appropriateness

- How do program activities address and relieve financial trauma?

- How does the program engage cultural attitudes toward money?

- Effectiveness

- To what extent does the program help families obtain knowledge and ability to handle personal/family finance?

- To what extent does the program help families approach housing stability?

- To what extent does the program help families obtain financial health through money management (i.e., savings, budgeting, and investment)?

- Efficiency

- To what extent do resources (i.e., program coordinator(s), program administrator, and program budget) lead to expected output and outcomes?

This evaluation sought to account for the feedback and perspectives of different stakeholders that participated in the pilot.

- Target population: the families participating in this pilot program

- The current families sheltering at PSP

- The incoming families enrolled during the pilot period

- Service providers and administrators

- PSP staff

- Program coordinator

- Community partners and volunteers

Procedures

Current and former shelter families learned about how to design an evaluation plan during the sixth FFEC action committee meeting. The knowledge acquired from this presentation was put into practice in which committee members had the opportunity to collaborate with CURA to develop the evaluation plan for the FFF program. Four primary data collection methods were selected to evaluate the effectiveness of this program: document analysis, observations, surveys, and interviews. All drafts of the evaluation tools were shared with the FFEC Action Committee for feedback. These methods were collected throughout different phases of the FFF program.

During/Shortly After Completing Program

The program coordinators of the FFF program supported data collection throughout the duration of this pilot program by keeping records of participants’ profiles, direct, and indirect services provided, as well as the date and content of services. A document analysis was conducted on the records kept by the program coordinators in order to better understand the families engaged in this program and the extent to which the program was delivered. Information on participant’s profiles were documented during the intake process. Additionally, the program coordinators developed a participant tracking database which housed information on the types of program features and evaluation components completed by each participant. This database was continuously updated by the program coordinator and CURA.

Observations were conducted to better understand the class environment and the process of the delivered classes and services. CURA observed recorded sessions of the intake process and all four financial literacy classes during the start of this pilot program. Memos were written by two CURA graduate research assistants for each recorded video which focused on summarizing these sessions in addition to identifying key themes and quotes.

The program coordinators were responsible for administering surveys to participants pre- and post-participation. The pre-participation survey was administered to participants during the intake process or at the end of the 15-day grace period (refer to Appendix G). Upon completion of the program, the participants were administered the post-participation survey (refer to Appendix H). The pre- and post-participation surveys focused on better understanding the changes in families’ financial attitudes, knowledge, and skills in addition to their general experience in this program. These surveys were completed on paper. CURA was responsible for entering this data into the pre- and post-participation survey responses spreadsheet as participants enrolled and graduated from the program.

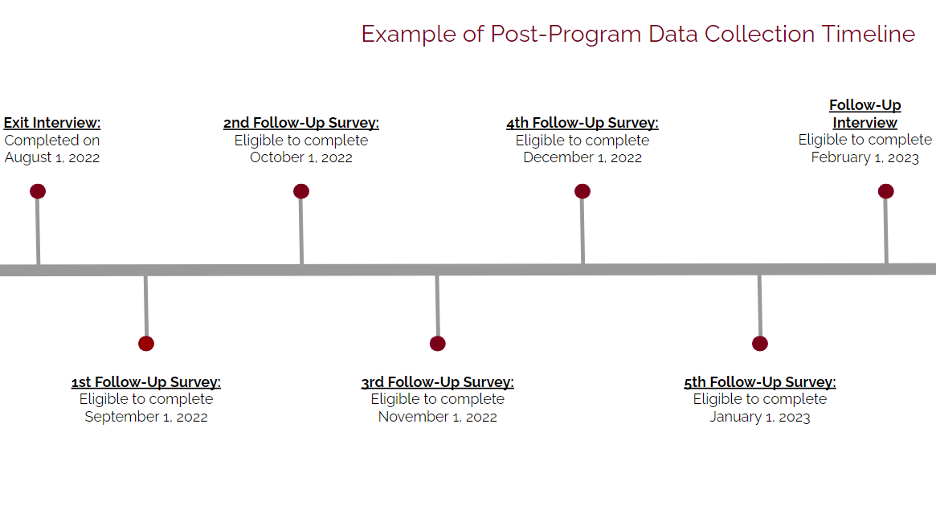

Post-Program

CURA conducted interviews and surveys as a part of the post-program evaluation. Participants were invited to complete an exit interview after graduating from the program and completing the post-program survey (refer to Appendix I). This exit interview focused on participant’s experiences with the program features and examined their plans upon graduating from the program. This provided the opportunity to gain an in-depth understanding of how the FFF program supported participant’s financial health, challenges that required additional support, and how this program should be improved for future implementation. An alternative exit interview was offered to participants who did not complete the program and returned to the Self -Pay policy at a later point in time (refer to Appendix J). The purpose of this exit interview was to better understand the reason that they are forced, or choose to go back, the obstacles they’ve encountered, their future plans, and the additional support that they may need. CURA kept in contact with the program coordinators to learn about each participant’s exit date. Participants were invited to complete the exit interview via phone, text, and email. Contact attempts were documented in a post-program participant tracking database developed by CURA. To maintain flexibility, participants were given the option to meet with CURA via Zoom, chat over the phone, or in-person. CURA informed the program coordinator after each exit interview was completed. PSP is responsible for distributing $25 to participants upon completion. CURA entered the completion dates into the participant tracking database developed by PSP as well as the post-program participant tracking database. Memos were written for each exit interview which focused on summarizing the interviews as well as identifying key themes and quotes.

Participants were invited to complete monthly follow-up surveys over the course of five months after completing the exit interviews (refer to Appendix K). The purpose of the monthly follow-up surveys was to track changes in participant’s challenges, plans, and outcomes after exiting shelter. Information on the opening dates of the monthly surveys was tracked on the post-program participant tracking database. An electronic survey link was distributed via email or the questions were read aloud over the phone and manually entered by CURA. Calls, texts, and email reminders were sent if needed. Contact attempts were documented in the post-program participant tracking database. The program coordinators were notified upon completion of the follow-up survey. PSP was responsible for distributing $10 to participants for every survey completed. CURA entered the completion dates into the participant tracking database developed by PSP as well as the post-program participant tracking database.

Participants were invited to complete a follow-up interview six months after completing the exit interview (refer to Appendix L). The purpose of the follow-up interview was to explore changes in the participant’s living conditions and financial health. This interview focused on whether the FFF program was helpful in reducing recidivism, improving participant’s financial health, and contributing to housing stability. Information on the opening dates of the follow-up interviews were tracked on the post-program participant tracking database. Participants were invited to complete the follow-up interview via phone, text, and email. Contact attempts are documented in the post-program participant tracking database. In order to be flexible, participants were given the option to meet with CURA via Zoom, phone call, or in person. CURA informed the program coordinator after each follow-up interview was completed. PSP was responsible for distributing $25 to participants upon completion. CURA enters the completion dates into the participant tracking database developed by People Serving People, as well as the post-program participant tracking database. Memos were written for each follow-up interview which focused on summarizing the interviews as well as identifying key themes and quotes.

An example of the post-program data collection timeline can be found here:

Figure 2. Example of Post-Program Data Collection Timeline

End of Pilot Program

CURA conducted exit interviews with program partners toward the end of this pilot program (refer to Appendix M). The purpose of this interview was to better understand program partner’s experiences with the development, implementation, and administration of the FFF program. The exit interviews focused on the successes and challenges associated with this program from the perspective of program partners who provided direct leadership and support throughout this process. An email invitation to participate in this exit interview was sent to People Serving People leadership, the program coordinators, and the Hennepin County shelter team. Participants were asked to complete a demographics survey and consent form prior to the interview date. All exit interviews were completed in August of 2022. Memos were written for each exit interview which focused on summarizing the interviews as well as identifying key themes and quotes.

Data Collection Challenges/Limitations

COVID-19 presented a challenge with conducting on-site observations. CURA initially planned to visit the emergency shelter in order to observe one-on-one counseling meetings, financial literacy classes, and any additional trauma-informed group activities provided to participants. As a result of a COVID-19 outbreak, these plans changed to protect the health and safety of shelter families. The program coordinators video- and audio-recorded the intake process in addition to each financial literacy class.

Additionally there were challenges with contacting participants for the interviews and monthly surveys. The initial goal for completing the exit interviews was one month after participants graduated from the program and completed the post-program survey. Over the duration of several months, some participants were non-responsive to multiple contact attempts before completing the exit interview. On at least one occasion, a participant was non-responsiveness due to being a single mother with no social support and having multiple responsibilities. CURA continued to reach out to participants past the one-month deadline. Similarly some participants needed additional time to complete the monthly follow-up surveys. To maintain flexibility, the survey was distributed a few days prior to the monthly opening date. Reminders were also sent if needed.

The program coordinator responsible for leading the administration of the FFF program left People Serving People in July of 2022. CURA was unable to coordinate a time to meet for the exit interview prior to her departure. This was the only exit interview with program partners that was not completed.

Key Findings

Model Development Results

Participant-Driven Program Elements

Engaging current and former shelter guests in the development of the FFF program resulted in particular insights and nuance that we believe contributed to a model that is distinctly responsive to the needs of current and future shelter guests. While many of the components of the FFF program were informed by or adapted from existing programming, in review of the action committee meetings we observed four unique program elements that participants advocated for, including 1) addressing “financial trauma” prior to engaging in financial literacy activities, 2) prioritizing partners with lived expertise, 3) seeking communal healing and peer accountability, and 4) embedding individualization, choice, and flexibility into the model.

Financial Trauma

During the first FFEC action committee meeting, there was a robust discussion about the importance of understanding each person’s relationship to money before initiating any activities to build financial literacy. The group discussed that one’s understanding and relationship to money is established at a young age, often through cultural values and family experiences and that until individuals understand how they psychologically associate with money, it is very difficult to improve financial literacy.

Below are a few key quotes from action committee members as this idea emerged:

“My family, they are gamblers like for real, for real yall, they live on the reservations okay? For real. The casinos they, live there. And it is sick, it’s been sick since I was a kid, but here’s the thing with my family they all either are retired veterans who went on to get jobs, have retirement benefits um in the healthcare profession, um my mom is teacher, masters…so it’s like there’s a whole lot of educated gamblers is where I come from. They invest, but they blow money at the same time, so it’s like, I am right there on that scale I’m where, I get exactly what you’re saying because my relationship with money, pshh I blow money okay I’m not even going to sit here and sugar coat it like I don’t.” -Action Committee Member

“As a Native American, I, my family is extended on past grandparents and great grandparents so um there is a responsibility with that money, that I have to stretch each dollar, each penny and each dollar, so how do I do that and how do I look toward the future so that I don’t have to work so hard any more?” -Action Committee Member

“When we talk about family, and or friends even, um not having it myself I extend some kind of guilt towards them not having it and sometimes risk my own financial stability by helping out other people. And so, ‘cause I don’t want to hear the word ‘no’, I’ve heard that, you know in denial as my Black life in the state of Minnesota, where we have the highest racial disparity, and systematic, that um there was like um a sense of subconscious guilt, like you know, I gotta help them, you know and I’ll figure me out later, you know it’s… yeah it is um … some trauma around especially um with Black and Brown folks um around money and how we just really are always trying to help each other…sacrificing a lot” -Action Committee Member

The action committee began to refer to these experiences as “financial trauma.” This was a key insight for the development of the FFF program as participants decided that addressing financial trauma was an essential prerequisite to any financial mentorship or literacy embedded in the program.

Identifying a qualified external partner that could effectively build and facilitate a curriculum that engaged with financial trauma became a pillar of the FFF program design. However, finding a financial education partner with a strong understanding of community trauma proved to be one of the greatest challenges in the model design phase. We suspect that while financial trauma is an often overlooked aspect of traditional financial literacy/financial empowerment curricula, it may be a powerful ingredient, particularly for Black and Brown communities who have experienced and presently experience systematic financial exclusion and oppression.

Lived Experience

Throughout the action committee meetings, participants discussed the importance of ensuring that the individual delivering the financial empowerment program had lived experience, both to support building connections with participants, but also to infuse storytelling and real world examples into the curriculum.

One action committee member suggested, “If we had more people who’d been through homelessness and everything, working on, I mean like successful people and like role models, working on families working with families individually, I think it’d be real good. And I think it should be some type of policy where we look for those type of people that been through it, that’ve been through the homelessness, have a better outlook and a better understanding” -Action Committee Member

The program coordinator who was selected to administer the FFF program had worked at PSP for more than 12 years and had the desire to support families due to her own lived experience. Multiple program participants commented on how her expertise fostered trust and mutual understanding.

Communal Healing and Peer Accountability

Program participants discussed the fact that entering shelter can be isolating and traumatizing. One way the action committee identified to address these challenges was to intentionally build connections and support networks through this financial empowerment program. The action committee discussed the value of building accountability by pairing shelter guests with one another in order to attain individualized goals and to facilitate opportunities for communal healing while in shelter.

Individualized Programming, Family Choice, and Flexibility

One PSP staff member shared regarding the action committee meetings, “it was clear that families wanted choice. They wanted an ability to have options about whether to participate or not, whether to self-pay or not.” -Action Committee Member

“We should be looking at families individually to see exactly what they need.” -Action Committee Member

“Only I know what my family truly needs on a day to day basis and a financial empowerment program would allow me to make those decisions” -Action Committee Member

One key program element incorporated into the FFF program in alignment with this value is the individualized care plan. Each program participant is required to complete an individualized care plan that accounts for the particular circumstances and traumas each participant has experienced. The group suggested that by prioritizing the needs most relevant to families, the FFF program would enable financial empowerment activities to be more effective and sustainable.

“Everyone has different issues within themselves and so one person might feel like mental health is good for them, the next person might feel like financial is where they’re lacking and so its best for them, so it depends on the individual” -Action Committee Member

The action committee expressed early and often the need for an effective program to adapt and respond to the specific needs of families as they maneuver the crisis of entering shelter. One particular program element that corresponded to this value was the inclusion of the initial 15-day grace period. The grace period is a 15-day period at the beginning of the FFF program in which participants are given time to adjust to their transition to the shelter and to make an informed decision about whether to participate in the pilot financial empowerment program. Some of the programs the action committee reviewed as part of the landscape scan of existing self-pay or financial empowerment programs included a grace period.

In the fourth committee meeting, one action committee member said of an LA Mission program, “I also like the 1-month grace period because um I really feel like that is a great time for people to like get a bearing, get a grip, let alone decide whether or not to be in any program, but to actually have a respite moment.” -Action Committee Member

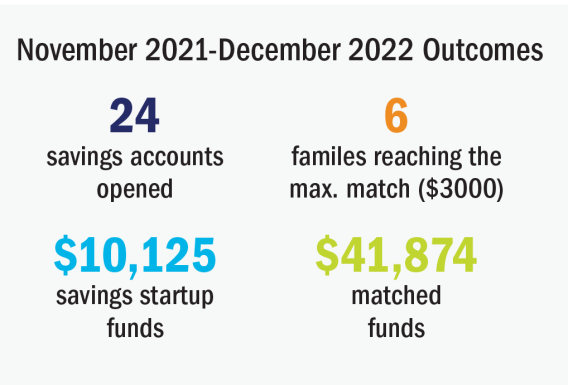

Model Execution Results

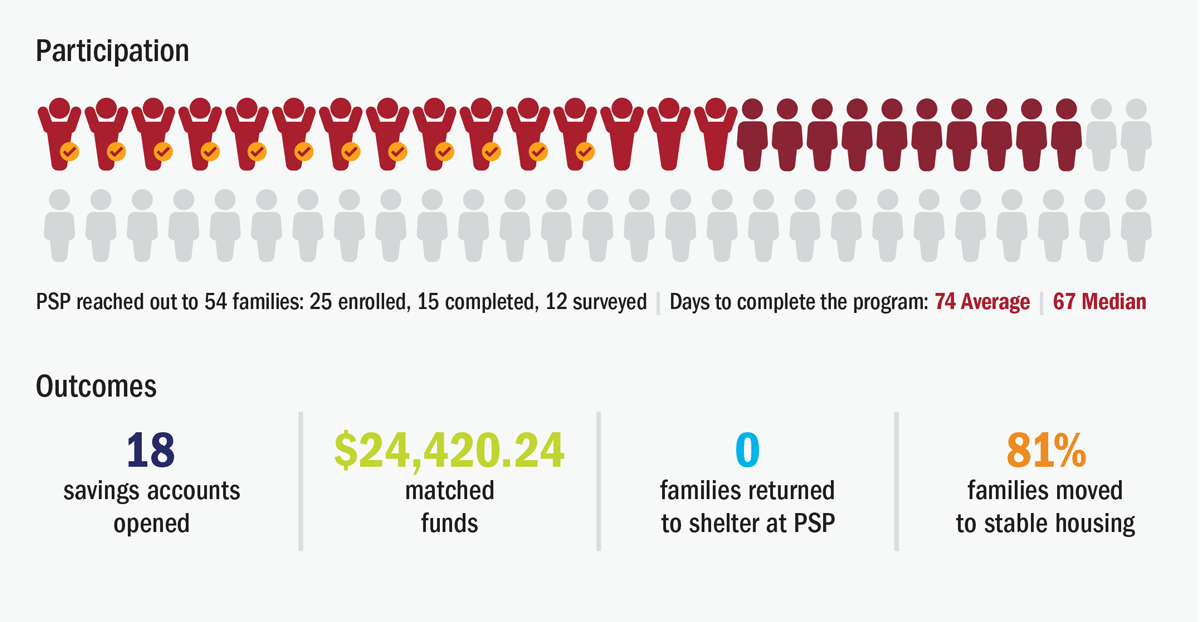

Between November 2021 and April 2022, 25 participants agreed to participate in the pilot program and the corresponding evaluation Out of these 25 participants, 15 were able to successfully complete all of the program components. For the purposes of the evaluation, completing the program entailed 1) completing an intake, 2) developing an individualized work plan, 3) attending all four financial classes, 4) creating a savings plan and 5) completing one month of savings.

Originally, the program was offered to 54 participants; however, some of the participants ultimately were unable to participate in the program. In order to begin analyzing data, PSP stopped offering the program for research purposes after April 4, 2021. However, they continued to enroll participants after that date in the program but without the research component.

Prior to COVID-19, our original intent was to have a much larger population enrolled in the pilot. However, as shelter policies evolved and shifted throughout the pilot period, our eligible participant pool became more complicated. Specifically, the elimination of the self-pay policy significantly reduced the incentive for participants to engage in the pilot. Because of the small number of participants, we are hesitant to make conclusive statements about the FFF pilot program. Instead, we seek to highlight observed successes and challenges, areas of participant satisfaction and feedback, and opportunities for further investment.

| FFF Pilot Program Completion Data | November 2021 and April 2022 | |

| Total # of Families PSP reached out to | 54 |

| Total # of Families accepted and enrolled in the FFF program | 25 |

| Total # of Families that completed the FFF | 15 |

| Total # of Families that completed the Post-Program survey | 12 |

| # of Savings Accounts Created | 18 |

| Dollars Matched | $24,420.24 |

| Outcome Data for Families that Completed the FFF Program | |

| # of Families who have returned to shelter at PSP | 0 |

| % of Families who moved to stable housing | 81% |

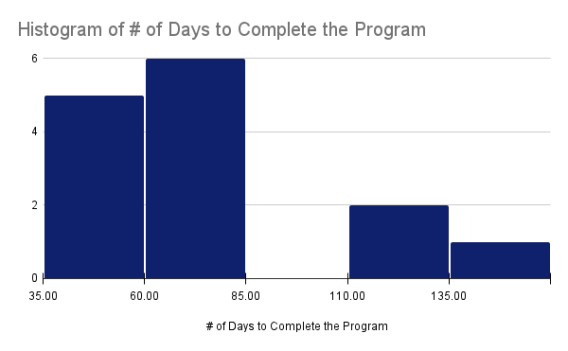

Average Number of Days to Complete Program: 74 days

Median Number of Days to Complete Program: 67 days

Figure 3: Days Participants took to Complete the Program

Motivations for Enrolling in the Pilot

There were a number of reasons participants gave for enrolling in the FFF pilot program. A majority of the participants expressed a desire to either gain budgeting or saving skills for themselves and their families; however, many participants also identified the opportunity to preserve their own income and to receive a savings match as key motivators for the program. We think PSP could tailor recruitment materials to align with these stated motivators when considering future program enrollment.

Improve Financial Literacy To Improve Financial Stability

Four participants stated that they wanted to increase their financial literacy by learning more about how to save and manage money. One participant explained that the main reason she decided to participate in the program was that she believed it would be important and beneficial for her to learn specific financial skills.

“The reason why I chose it is because I thought that it would be really helpful for me to learn how to save and have financial literacy under my belt and also get the information that I needed to become debt free.” - FFF participant (Black, Female, 29)

“Because I think it will be beneficial and I will be able to budget my money so that I am not living check to check.” - FFF participant (Black, Female, 33)

Improve Opportunities for Children

Two participants specifically identified improving opportunities for their children as the motivating factor for participation. One participant indicated that she did not wish for her children to go through what she experienced growing up as she was always worried about her family’s financial health.

“I want to secretly save something to help them. I want to buy property. So those are my future goals.” “I want them to be able to lean on me. That is why I am doing certain things now so that I can be more stable.” - FFF participant (Black, Female, 27)

“I want to give my kids a better outlook on how to manage money and save money because it is important.” - FFF participant (Black, Female, 26)

Savings Match and Income Preservation

Many participants identified the ability to keep their income and receive matching funds after completion of the program as the primary motive for program participation.

“What caught my eye was that I wouldn’t have to self-pay. I didn’t know anything about the program really. I just realized that I didn’t have to self-pay - that is a blessing you know.” - FFF participant (White, Female, 41)

One participant suggested that the “massive savings” was what attracted her to the program. - FFF participant (Black, Female, 28)

One participant suggested that because the savings was her primary motivator, she wanted to skip resources that were not required to complete the program; for example receiving assistance with developing a resume.

“I was not focused on the classes. I was focused on matching and getting the full amount.” - FFF participant (Haitian, Female, 32)

Reasons for Exiting the Program

There were various reasons provided from participants who declined to engage with the program. For example, some moved out of shelter before being able to enroll and therefore were no longer eligible. For others, they simply did not engage with PSP after initial contact despite outreach efforts by PSP.

PSP conducted outreach to understand why individuals either did not engage with the program from the beginning or exited the program midway through and learned that 1) work schedules, 2) childcare, and 3) other priorities were common reasons for disengagement.

Since the FFF program sessions are held during normal workday hours, there is a possibility that those who found work while in the program might not have been able to attend the scheduled class sessions. Furthermore, children are not allowed in group class sessions. There are child care options provided at PSP, however participants need to enroll in those services and sometimes there is a waitlist. Finally, individuals entering a shelter can be inundated with services, programs, and activities. Depending on individual needs, availability, and other factors, some participants were unable to prioritize the FFF program on top of the other priorities. Rationales for exiting the program can also be important to consider for future iterations of the program.

FFF Program “Appropriateness,” “Effectiveness,” and “Efficiency”

As stated in our methods description, the primary FFF program factors we evaluated were the “appropriateness,” “effectiveness,” and “efficiency” of the FFF program. We evaluated these factors through class observational videos, reviewing and summarizing meeting notes, review of available data, exit interviews with program participants, and post-participation survey results. Out of the 15 participants that successfully completed the pilot program, our team was able to reach only seven participants to complete the exit interviews to get their feedback and opinions on the program. Our research team found it challenging to get in touch with families after they had moved out of shelter because contact information has often changed, families may have other obligations, or sometimes families wanted to close that chapter of their lives.

Appropriateness

We identified two major questions to evaluate whether the FFF pilot program was “appropriate.”

- How do program activities address and relieve financial trauma?

- How does the program engage cultural attitudes toward money?

The Network trained PSP staff to introduce financial trauma by explaining how trauma can be experienced on an individual, group, or societal level; in particular, identifying collective trauma, intergenerational trauma, and historical trauma.

Participants commented on how the concept of financial trauma resonated with their experiences. One of the participants emphasized how she really enjoyed the session on financial trauma and that they were “On-spot” for her. Another participant related how the discussion of financial trauma resonated for her,

“That was something that I feel wasn’t really talked about. I think financial trauma is way bigger than people understand. I think if you just give somebody money with a little bit of information they will continue the habits they had….Even before that I realized that was something that exists and I’ve been trying to work on. So I did find that interesting that that was brought up” - FFF Participant (Haitian, Female, 32)

Another participant indicated that the Financial Empowerment class, especially the financial trauma sections were “definitely a big eye opener for me. I don’t think I really never thought about my connection to money as far as my family is concerned, and then, when I actually looked at it, it made sense the way that I handle money today. It definitely made sense.” -FFF Participant (Black, Female, 28)

The FFF model utilizes the example of redlining in Minneapolis to demonstrate how systemic racism impacts Minnesotan’s financial trauma as well as other forms of trauma. This particular example helped one participant to consider how financial trauma may have impacted her and her community.

“The red lining and how like you know there’s so much property in one area. In so, it just makes you want to do more, you know, in the community, it makes you want to be a part of the solution and not the not the problem you know it gives you answers to your questions that you that you’ve had for so long, also.” -FFF Participant (Black, Female, 29)

Furthermore, as part of the post-participation survey, 83 percent of respondents who completed the program suggested that the FFF pilot program was “to a great extent” successful at addressing “financial traumas and experiences identified” and that participants had “started to heal.”

While many participants indicated that the discussions of financial trauma were beneficial and resonant, some found the topic to be challenging and uncomfortable. A few participants indicated in the exit interview that this session made them uncomfortable as they were asked to confront particular experiences, cultural or family norms, etc. A few participants also mentioned their general discomfort in being asked to speak about very personal topics. Originally the program had been designed to be conducted in a group setting, but had to switch to 1:1 because of COVID-19. We are curious whether engaging in vulnerable topics as a group may have made sharing easier and may have mitigated some of this stated discomfort.

Based on the feedback provided by participants along with the observational videos, the evidence suggests that the FFF pilot program and its curriculum provided “appropriate” information to better understand one’s financial trauma and to begin to engage with cultural attitudes toward money. However, the feedback regarding discomfort discussing these sensitive topics offers an opportunity to modify the curriculum to address, mitigate, or more effectively manage this unease.

Effectiveness

We identified three major questions to evaluate whether the FFF pilot program was “effective.”

- To what extent does the program help families obtain knowledge and ability to handle personal/family finance?

- To what extent does the program help families approach housing stability?

- To what extent does the program help families obtain financial health through money management (i.e., savings, budgeting, and investment)?

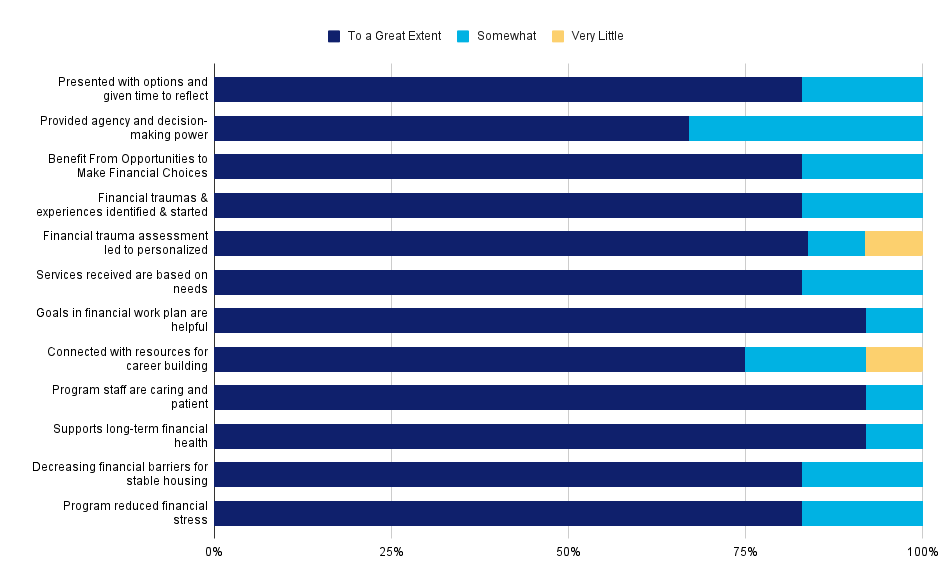

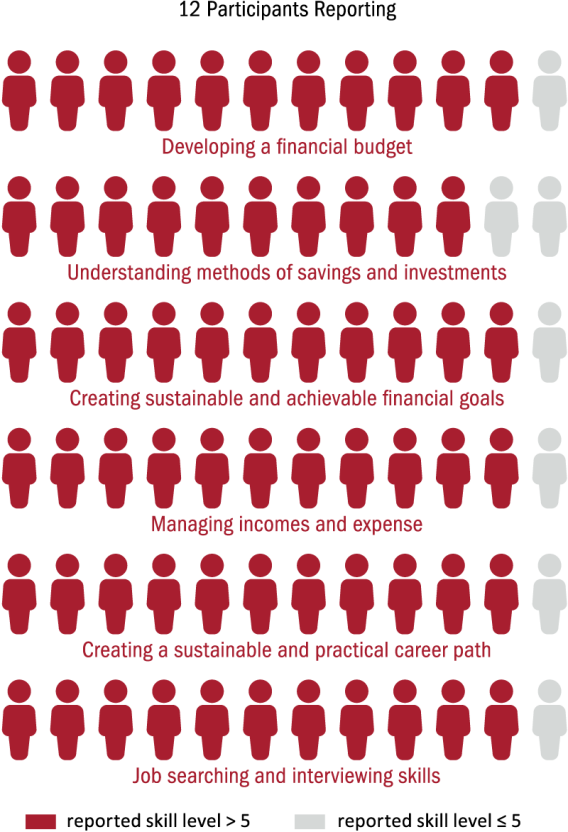

Below is information from a survey administered to the participants after their completion of the Family for Finances program. The purpose of this survey was to develop a deeper understanding of how the participants perceived the different components of the program and its overall effectiveness.

The sample size in this case is the number of participants who responded to the post-participation survey which is 12 participants. (N=12)

Program Effectiveness

The post-participation survey included questions such as: To what extent do you think the program was successful in taking care of the following items?

- I have been presented with options and given time to reflect and make decisions.

- I have been provided with agency and decision-making power.

Figure 4: Program Effectiveness Post-Pilot Survey Results

There were only two areas for which less than or equal to 75 percent of participants found the program to be very effective at supporting. When responding to the statement “I have been provided with agency and decision-making power,” only 67 percent of respondents indicated that the program was “to a great extent” successful at addressing this and 33 percent of respondents suggested that the program was “somewhat” successful at addressing this. When responding to the statement “I have been connected with resources for career building,” only 75 percent of respondents suggested that the program was “to a great extent” successful at addressing this, 17 percent of respondents indicated that the program was “somewhat” successful at addressing this, and eight percent of respondents suggested that the program had “very little” success at addressing this.

These broadly positive survey responses offer some evidence of the program’s effectiveness, but also an opportunity to explore targeted areas for improvement. Specifically, responses suggest PSP could investigate strategies for enhancing agency and decision-making power, connecting with tangible career-building resources, and potentially additional opportunities for personalizing the financial trauma assessment.

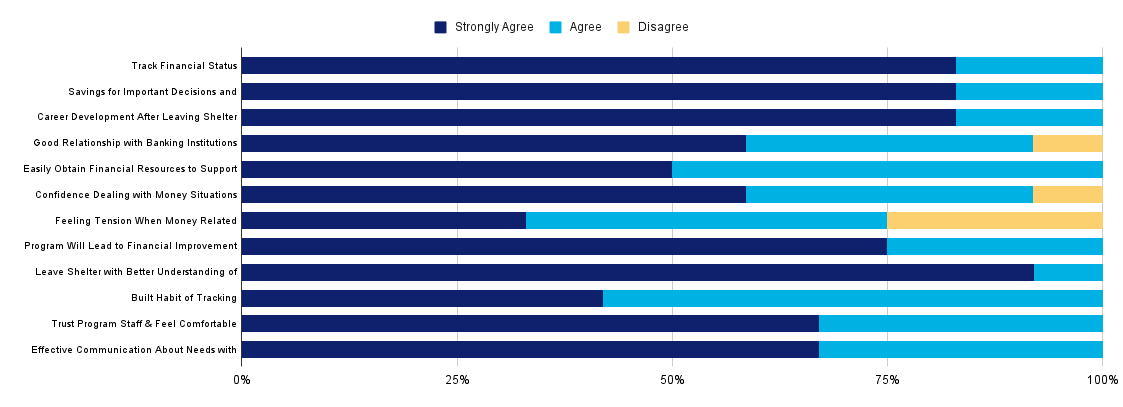

FFF Pilot Alignment with Original Program Goals

The following survey questions were aimed at determining whether the programmatic goals identified by the FFEC action committee were realized in the FFF pilot program.

To what extent do you disagree or agree with the following statements by reason of participation in the FFF program?

- It is necessary to track personal and family financial status.

- A person or a family needs to use savings for important decisions and emergencies.

Figure 5: FFF Pilot Program Alignment with Proposed Goals

The four areas for which participants responded that they had the least confidence or ability to manage following the FFF program were:

“I can easily obtain financial resources to support my family”

A lack of confidence in participant’s ability to obtain financial resources to support their family suggests that participants may need additional investment or support related to education or career-related resources. It could be worth PSP further exploring what additional resources would facilitate participants feeling more confident in this area.

“I built the habit of tracking my personal and family’s financial status”

For some participants, developing strategies for tracking personal finances may be a new skill area. PSP could consider what supports could be put in place to support families to continue to strengthen this habit even after they exit shelter.

“I am confident when dealing with situations that involve money”

“I have a good relationship with banking institutions”

These two responses are likely related to historical experiences with finances and financial institutions. While the FFF program seeks to begin to address financial trauma, it makes sense that participants may just be beginning to heal from their financial trauma. However, it again presents an opportunity for PSP to work with former pilot participants to consider ways in which to ensure healing from financial trauma is ongoing even after exiting the program.

Knowledge and Ability to Handle Personal and Family Finances