Author: Principal Investigator, Dr. Brittany Lewis, Senior Research Associate

Contributing Authors: Dr. Shana Riddick, Arundhathi Pattathil, Keelia Silvis, Peter Schuetz, Yue Zhang, Justin Baker

Project Funders: Brooklyn Park Economic Development Authority, City of Brooklyn Park; Hennepin County; and State of Minnesota, Minnesota Housing Finance Agency

Looking for the Brooklyn Park Housing Project Executive Summary? Click here.

Report Overview

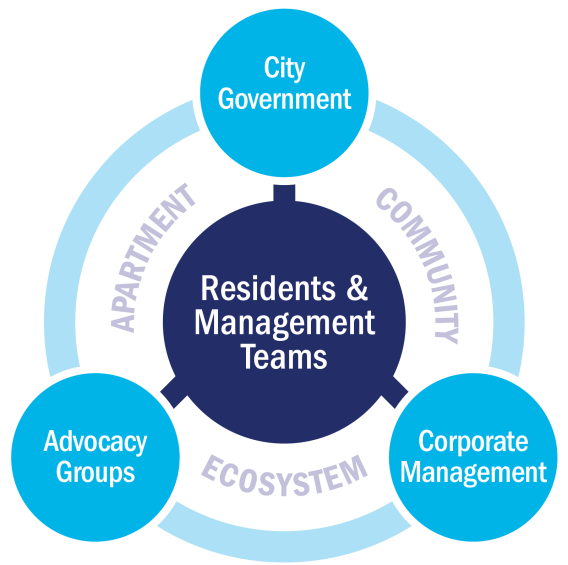

The Brooklyn Park Housing Project was enacted to examine experiences in the city’s large apartment communities—specifically within its “apartment corridor.” During one-on-one meetings with community stakeholders at the start of this project, one of the pain-points repeatedly shared was the divide that commonly exists between city renters and homeowners and that more was needed to better understand and respond to the realities of city renters. There was a strong desire for a qualitative study that would center project participants’ voices. The project’s Advisory Council, guided by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) research team, moved through a process where they collectively developed the project framework and its accompanying research tools. A research project can take multiple directions. This process began with a clear understanding that this would be a housing study that examined conditions in the city’s large apartment communities, but beyond that point the Advisory Council determined its framework. Ultimately, the project focused on relations amongst tenants and management, safety and security, and tenant/management members’ understanding of their rights and responsibilities. Examining the quality of one’s housing experience (resident) and working environment (property management team member) grounded this work. No research project can answer all questions or address every pertinent area of focus. The human experience exists within a multifaceted ecosystem, and a research project provides an opportunity to examine a facet of those complexities.

The central objective of this project was to humanize the experiences of renters (and in effect present the working environments of property management team members) by addressing social conditions, relationships/interactions, and the role of educational opportunities (i.e., understanding one’s rights), which shape life within the city’s large apartments. This is not to say that issues regarding affordability, economic development, education, or youth services are not essential to experiences in the city’s large apartments, but they were not the lens and direction in which the Advisory Council chose to move. Studies examining these topics should be commissioned and where applicable, analyses examining these areas appear in this report. First and foremost, this report introduces the experiences of renters and property management team members, examining what it’s like to live in these communities, raise children, or work within them.

Introduction

“I moved here and stayed here because I love the fact that I live two blocks away from Riverview Park, and it’s beautiful—it’s lovely. I bring my bike there now. I hike there. And when I was going through some mental health challenges my partner and I would go there and walk.” (BP21, resident)

“I’m a single mom. For me, it’s not just about me and my four walls of a home. It’s [about] knowing my neighbors; it’s [about] feeling safe with my neighbors if something happens; feeling secure that they would call the police and say, ‘Hey, I know she’s a single mom, or I haven’t seen her in a couple of days, well, what if something happened?’” (BP03, resident)

“I wanted to be on the affordable side with our families, who really needed the extra support and housing. I wanted to bring that passion to my sites. My teams and I really want to meet our residents where they’re at. We want to try and accommodate them too, whatever it may be—accommodation, as far as a modification to your home, whether you need resources for unpaid rent—whatever we can do.” (BP24, property management team member)

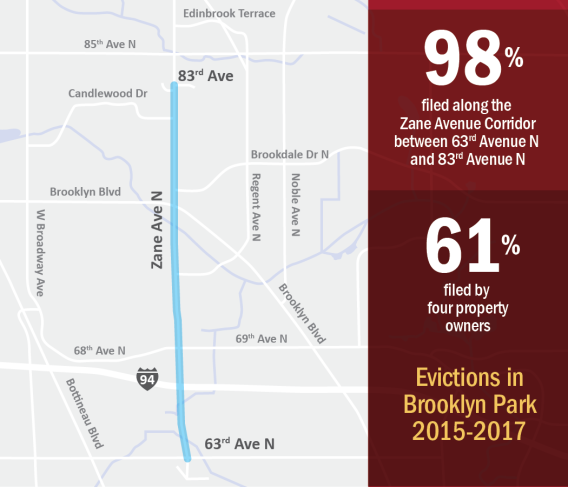

In July of 2016, the Minneapolis Innovation Team, in partnership with the nonprofit Minnesota tenant advocacy organization HOME Line, published a report on Evictions in Minneapolis, which was inspired by Matthew Desmond’s book, Evicted. The Innovation Team’s report found that 50% of tenants in the 55411 and 55412 zip codes were evicted in a two-year span. The report effectively identified eviction trends in the City of Minneapolis using quantitative data and mapping of a small sampling of eviction court case files. In August 2018, HOME Line, in partnership with CURA, completed a similar quantitatively focused analysis of evictions in Brooklyn Park and found that of the eviction cases filed in 2015 through 2017 in Brooklyn Park, 61% of eviction cases were filed by the top four frequent filer owner groups with most filings (98%) taking place along the Zane Avenue Corridor between 63rd Avenue North and 83rd Avenue North. These reports have enabled local policymakers and practitioners to begin the process of reshaping the narrative around evictions and helping to generate new and pressing questions many had not considered.

However, these reports did not take a comprehensive mixed methodological approach enabling community members, policymakers, and other relevant community stakeholders to address how and why these trends are taking place from the perspectives of tenants and landlords themselves. The Brooklyn Park Housing Study aims to better understand housing instability and quality of life in a select number of Brooklyn Park apartment communities for the purpose of producing tangible policy and practice recommendations that produce equitable outcomes.

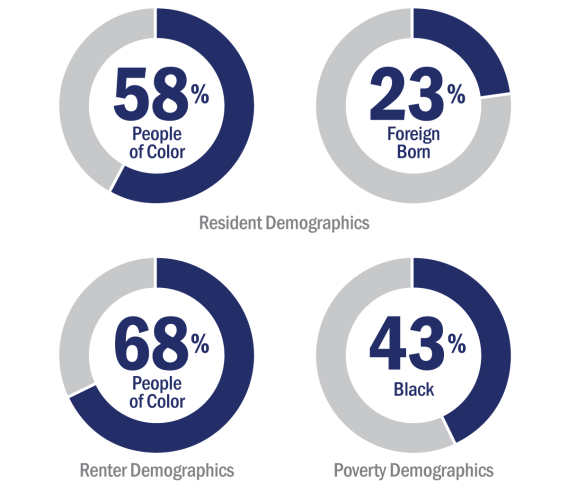

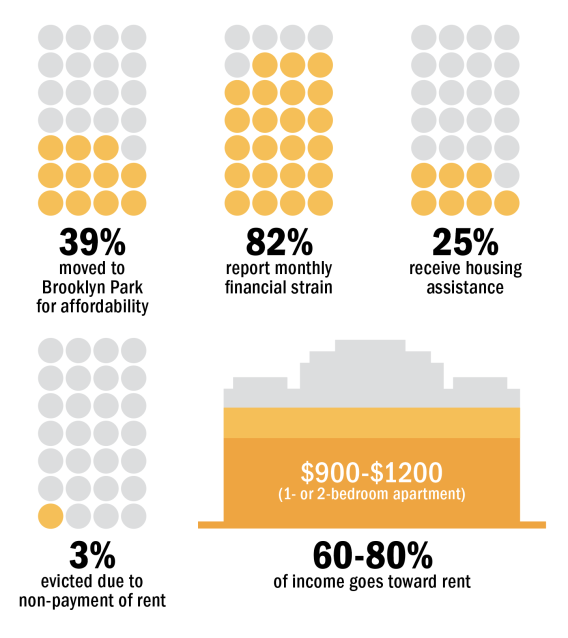

The Context: Rental Housing Stability and the Politics of Eviction in the City of Brooklyn Park

Brooklyn Park is a first-ring suburb of Minneapolis with people of color as a majority (58%). Specifically, 29% of Brooklyn Park residents identify as Black, 19% as Asian, and 6% as Hispanic or Latino (United States Census Bureau, 2019). Foreign-born immigrants comprise 23% of the population in this city, with a significant population from Africa (i.e., Liberia, Kenya, Somalia), and Southeast Asia (i.e., Laos, Vietnam) (The Minnesota State Demographic Center, 2018). Among the 30% of Brooklyn Park residents who are renters, 68% are people of color. Housing stability and quality of life are core concerns for rental apartment communities in Brooklyn Park. While evictions in Hennepin County decreased significantly over the past decade, the number of evictions in Brooklyn Park has stayed relatively stable. As stated above, in the eviction cases filed between 2015 and 2017 in Brooklyn Park, 98% took place along the Zane Avenue Corridor between 63rd Avenue North and 83rd Avenue North. Four property owners owning 28% of rental units accounted for 65% of eviction cases. In addition, property owners in Brooklyn Park had a relatively shorter grace period for late payment. On average, Brooklyn Park evictions were filed 16 days after the rents were due (HOME Line, 2018).

Although not all filings lead to displacement, an eviction filing remains on a tenant’s record for seven years. Further, apartment managers who do not use a screening agency may even see eviction filings beyond the federally mandated seven-year window. It means that even if an eviction filing does not end in an eviction or displacement, the filing itself has important consequences for households, especially for families of color. Therefore, seeking to reduce eviction filings and ensure stable housing is critical for the city. The solution to this problem is not simply to ban the eviction filings but to explore the root causes of the problem—why do people delay rent? How do renters come into the situation of being evicted? Have there been any attempts to resolve conflicts between property owners and renters through communication and relationship-building? Understanding the factors that lead to eviction filings and alternative pathways is essential to developing increased housing access, stability, and quality.

Quality of Life Issues Regarding Affordability, Safety, and Dignity in Brooklyn Park

The long-term sustainability of rental apartment communities and the quality of life for renters depend not only on reducing evictions. Affordability, safety, and dignity in housing are all fundamental concerns.

The Brooklyn Park Apartment Vacancy Survey (Kinara and Abe, 2019) shows that between 2016 and 2019 the median rent for one-bedroom apartments in the city increased 14% and the median rent for two-bedroom apartments increased 16%. The increased rent resulted in over half of the renter households being cost-burdened (i.e., spending more than 30% of their monthly income on housing costs) and a quarter of renters severely cost-burdened (i.e., spending more than 50% of their monthly income on housing costs). Driven by income level, housing cost burdens impact certain groups of the population more than others. With the median household income for residents at $74,000 per year and the per capita income at $32,000 per year, Brooklyn Park has a lower-than-statewide-average poverty rate (Minnesota Department of Health, 2017). However, poverty has been inequitably distributed by race in this city. Among all Brooklyn Park residents living below the poverty line, 43% are Black residents, higher than any racial identity (Data USA, 2020).

The City of Brooklyn Park has made efforts to address the affordability of housing. Over the past few years, Brooklyn Park has undertaken several newly developed housing policies and initiatives, including the Mixed Income Housing Policy, Fair Housing Policy, Tenant Notification Ordinance, and the Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH) Program, which aims to support the rehabilitation of unsubsidized rental housing affordable to people with incomes below 60% area median income (AMI). Brooklyn Park has the third largest NOAH property stock after Minneapolis and Bloomington in Hennepin County, and it has the highest proportion of NOAHs to total rental stock (83%) (Minnesota Housing Partnership, 2019b). Brooklyn Park’s vacancy rate is favorable to renters and has increased from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2019 (Minnesota Housing Partnership, 2019a).

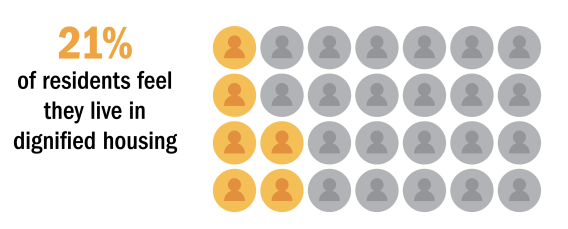

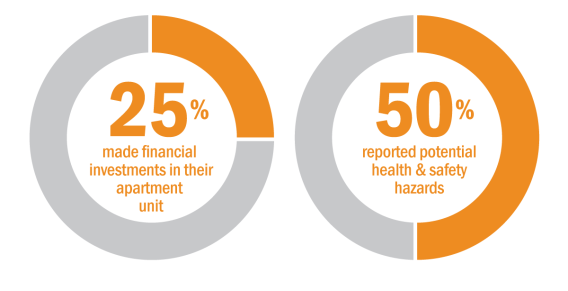

Despite these efforts, additional housing options and programs do not necessarily lead to a better quality of life for renters. In Brooklyn Park’s 2040 Comprehensive Plan (2021), the development and redevelopment of rental housing focus on small multifamily apartments and few units with three or more rooms. For larger households, the options are relatively limited. Regarding dignified housing, the housing quality issue has been concentrated in low-wealth communities and communities of color: 50% of renters with incomes below 30% AMI live in apartments with incomplete kitchens or plumbing and/or with too many occupants (Hennepin County, 2019). Other housing challenges and tenants’ rights issues include, but are not limited to: living in unhealthy quarters, being restricted by the city’s parking ordinances, and experiencing low-level inspection standards (ACER, 2019).

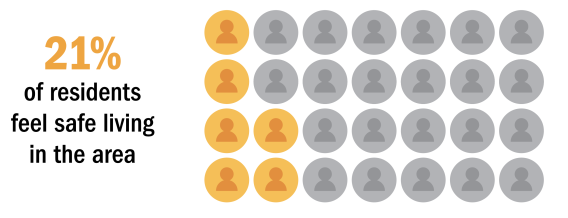

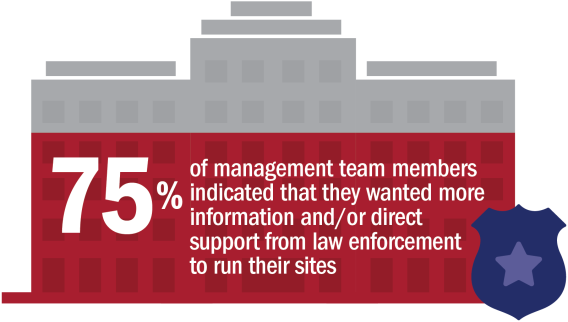

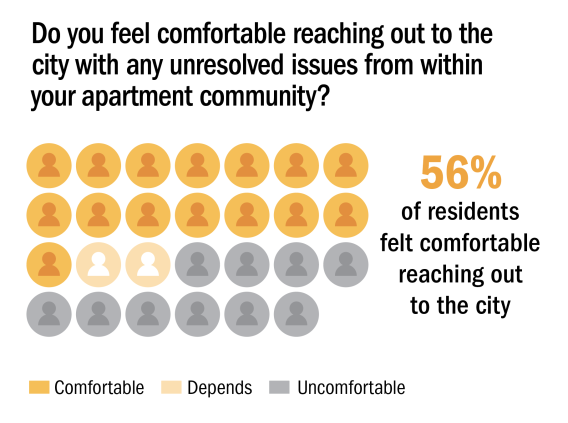

Besides affordability and dignity, safety and security is another concern in Brooklyn Park’s rental apartment communities. Hennepin County’s SHAPE Survey result (2018) shows that Brooklyn Park, along with other inner northwestern suburbs, has been the least likely to be strongly perceived as being safe from crimes and good for child-raising by local residents, compared to other parts of Hennepin County. The livable outdoor environment, the family and social relationship, and comparatively affordable rental prices attract people to reside in the city but they need more reasons to live and work here in the long term.

Valuing Voices and Experiences of Residents and Property Management is the First Step of Community Engagement

Stability, affordability, safety, security, and dignity in housing relate to the life and experience of every individual in the rental apartment communities, whose feelings, perspectives, and opinions should not be ignored. When addressing these issues, community engagement ensures that the exploration of factors is on the right track and policy decisions and solutions are fair and sustainable. In a city with a diverse population like Brooklyn Park, community engagement is particularly essential to direct the improvement of living conditions for all community members. However, housing and quality of life issues inevitably strain the relationships across residents, property management, and the city, which is an important condition for solving problems and enhancing community engagement. Valuing and including voices and experiences from residents and property management facilitates understanding, which is a critical step toward trust-building and future engagement.

Community members and policymakers need to address how and why housing issues exist in order to create proactive solutions. Quantitative analysis has uncovered a general picture of these issues, but it does not look into people’s daily lives and work and generate experiential knowledge from their perspectives. Therefore, it is important to apply the participatory design of action research to ensure that the key stakeholders are included in the process that renters are engaged, informed, and empowered, and property management team members who interact with them are valued and collaborated with in solving housing issues.

The Benefits from CURA’s Community-Based Action Research Approach

CURA believes that knowledge is generated from the communities. Research can only be transformed into actions through the participation and empowerment of community members and stakeholders. CURA’s principal researcher, Dr. Brittany Lewis, employs a community-based action research approach that uniquely disrupts the power imbalances that often exist between researchers and the community, particularly in communities of color and low-wealth communities. By engaging community members, a research project can 1) build community power, 2) assist local grassroots campaigns and local power brokers in reframing the dominant narrative, and 3) produce community-centered public policy solutions that are winnable and actionable.

The reciprocal relationships across sectors built through this model allow an open process where the participants stand on the common ground of a desire for social transformation. This actionable research model embraces a racial equity framework that asserts that we must 1) look for solutions that address systemic inequities, 2) work collaboratively with affected communities, and 3) add solutions that are commensurate with the cause of inequity.

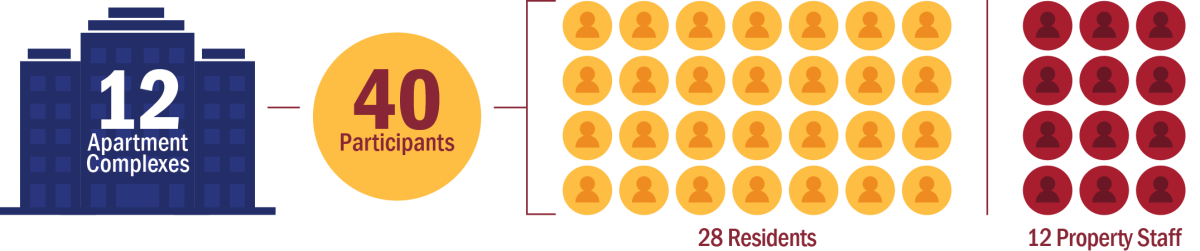

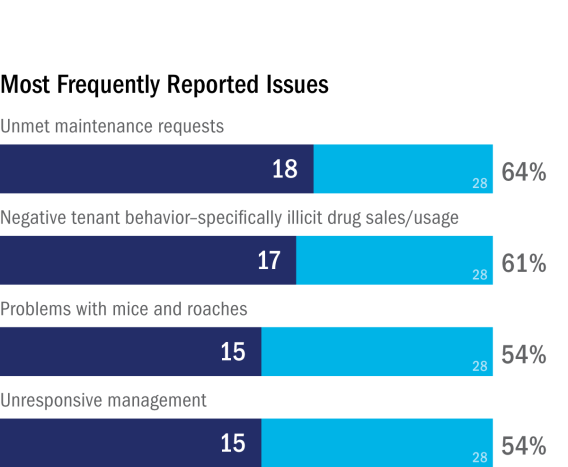

To explore root causes of housing instability, quality of life issues, and relationship-building challenges in Brooklyn Park rental apartment communities, CURA’s research team consulted with an Advisory Council primarily made up of diverse community organizations (e.g., African Career, Education, and Resource Inc. [ACER], HOME Line, Community Emergency Assistance Programs, Housing Justice Center, Community Mediation and Restorative Services), staff members from the City of Brooklyn Park, and staff members from Hennepin County. The background information and suggestions provided by the Advisory Council helped frame and shape the current research focus. In total, 28 residents and 12 property management team members, mainly from the Zane Avenue Corridor, were engaged in a comprehensive design of the inquiry. Knowledge generated from their lived experiences and opinions contributed to a racial equity lens and to developing community-centered solutions in policy and practice.

Report Sections

References

African Career, Education and Resource (ACER). (2019). Housing Gap Analysis.

Brooklyn Park 2040 Comprehensive Plan, Chapter 4 Housing in Brooklyn Park. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.brooklynpark.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2040-Comprehensive-Plan_NoAppendices_Chapter4.pdf

Data USA. Brooklyn Park, MN. (2020). Retrieved from https://datausa.io/profile/geo/brooklyn-park-mn

The SHAPE 2018: Hennepin County Adult Data Book. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hennepin.us/-/media/hennepinus/your-government/research-data/shape-2018/shape-databook-2018-v4.pdf

Hennepin County. (October 2019). Housing and Community Development Listening Session.

HOME Line. Evictions in Brooklyn Park. (April 2018). Retrieved from https://nwsccc-brooklynpark.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=5&clip_id=1322&meta_id=124417

Minnesota Department of Health. People in poverty in Minnesota. (2017). Retrieved from https://data.web.health.state.mn.us/poverty_basic

Minnesota Housing Partnership. (2019a). State of the State’s Housing 2019: Biennial report of the Minnesota Housing Partnership. Retrieved from www.mhponline.org/images/stories/images/research/SOTS-2019/2019FullSOTSPrint_Final.pdf

Minnesota Housing Partnership. (2019b). Market Watch: Hennepin County: Trends in the unsubsidized multifamily rental market. Retrieved from http://mhponline.org/images/stories/images/research/MarketWatch/HennepinCo/MarketWatchHennepinCounty.pdf

The Minnesota State Demographic Center. Data by topic: Immigration and language. (2018). Retrieved from https://mn.gov/admin/demography/data-by-topic/immigration-language/

United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Brooklyn Park, Minnesota. (July 2019). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/brooklynparkcityminnesota

Kinara, J. T. and Abe, S. (September 2019). Apartment Vacancy Survey Results for 2019. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynpark.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-rental-survey-results.pdf

Community Engagement Literature Review

Introduction

More than almost any level of governance, local government has the power and positioning to improve the communities they serve. The investments, mandates, and policies of local government can create flourishing futures. Community engagement ensures that governing decisions are equitable and sustainable solutions. This is especially true when addressing housing, a complex issue that intersects legal, social, economic, and health domains. In a place as diverse as Brooklyn Park, community engagement is critical to ensure that all community members can access safe, healthy, and dignified housing.

This document is designed to serve as a resource for Brooklyn Park local government. It will briefly summarize community demographics [Section II. Brooklyn Park], and it will then explain the fundamental importance of housing to the health and success of community members [Section III. Housing and Health]. These two sections can be used to explain and validate equity-focused housing reform pursued by Brooklyn Park’s leaders. This background is followed by a dive into and academic discussion of community engagement [Section IV: Community Engagement] and a legal overview of community engagement in local government [Section V: Context for Reform]. It ends with real-world examples of models to emulate and avoid [Section VI: Case Studies].

Brooklyn Park

Demographics

Brooklyn Park possesses vibrant racial and ethnic diversity.[1] Though only 20% of all Minnesotans are people of color,[2] approximately 57.5% of Brooklyn Park residents are people of color.[3] Specifically, 29% of Brooklyn Park residents identify as Black, 19% as Asian, 5.9% as Hispanic or Latine, and 4.5% as multiracial.[4] Strong immigrant communities also define Brooklyn Park’s demographic makeup, with an estimated 23% foreign-born residents compared to the statewide average of an estimated 8%.[5]

Socioeconomics

The median household income for residents in Brooklyn Park is $74,000 per year, and the per capita income is $32,000 per year. On average, poverty is lower in Brooklyn Park than Statewide, with 8.4% of residents living in poverty in Brooklyn Park compared to 9.5% for all Minnesotans.[6] However, poverty is inequitably distributed by race in Brooklyn Park, with Black residents bearing the highest poverty burden of any racial identity.[7] Despite Black residents only making up 29% of Brooklyn Park’s population[8], Black residents account for 42.8% of Brooklyn Park residents living below the poverty line.[9]

Housing

Approximately 30% of all housing in Brooklyn Park is occupied by renters.[10] Demographic information shows 68% of those renting in the city are non-white, compared to 40% of renters in Minneapolis and 36% of renters in all of Hennepin County. In 2017, there were an estimated 602 residential evictions filed against tenants in the City of Brooklyn Park. This number represents 7% of residential rental units within the city, which has 8,337 total rental units. However, this number underrepresents the residents affected by eviction because it does not reflect multiple family members involved in a single eviction, nor does the data capture informal evictions outside of the court process.[11]Another severe limitation of Brooklyn Park evictions data is that eviction courts do not record racial or ethnic information, so racial disparities in eviction rates must be estimated based on outside studies.[12]

Housing and Health

The Socio-Ecological Model

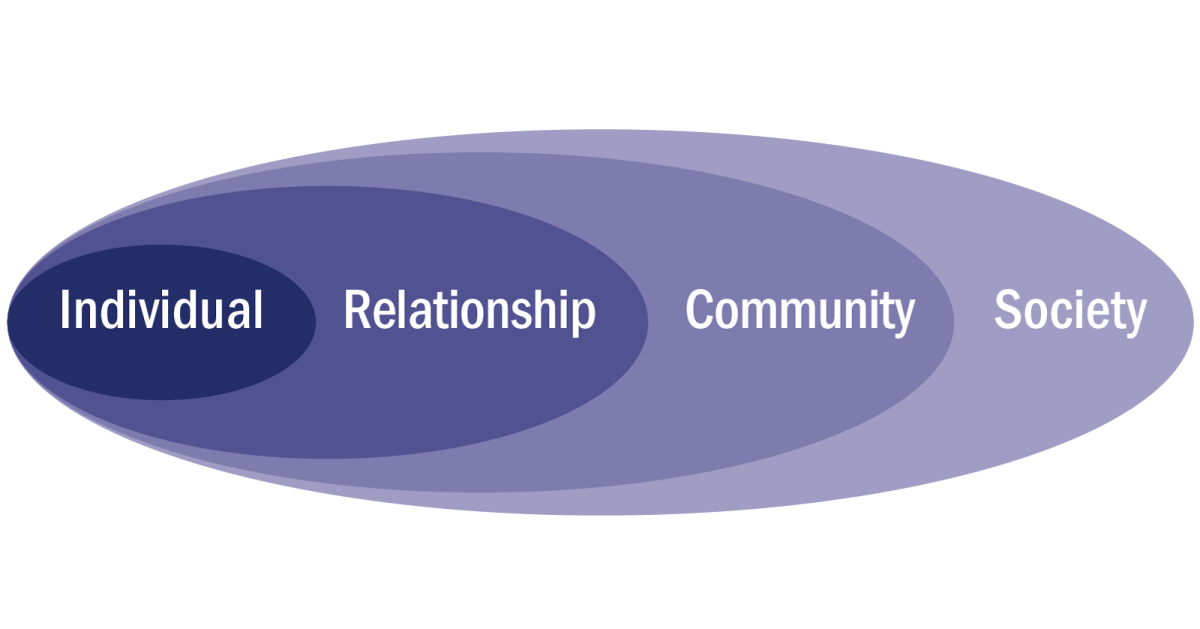

Housing has profound impacts on health and wellbeing.[13],[14] However, access to safe and dignified housing is not solely dependent on individual choice. As explained by the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM), an individual exists within the broader context of their relationships, communities, and the larger society [Figure 1]. Organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) use the SEM as a framework for prevention and intervention programs that target the social determinants of health (SDOHs).[15] By concisely defining the overlapping socially constructed systems that lead to health outcomes, the SEM helps to explain and frame the profound systemic disparities in the United States (U.S.) perpetrated against individuals and communities based on race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, physical and mental ability, and other intersectional identities.

For example, imagine a Black woman who has a physical disability and a White man who is able-bodied. Even if both make excellent health choices as individuals, differences in SDOHs will affect their resources, opportunities, and overall health. Regardless of her personal behaviors, the Black woman will experience disadvantages due to a lifetime of facing structural racism,11, 12 structural sexism,13,14 and structural ableism.15 To be absolutely clear: the Black woman can still live a vibrant and self-empowered life, and the White man can certainly experience adversity and suffering. However, because of their contrasting identities, the Black woman will face barriers to housing and health that the White man will never experience. The SEM has helped to frame countless CDC interventions to improve community health by addressing the broad context of a person’s life as well as their individual circumstances.[17]

Housing and Healthy Communities

The comparative example above was imaginary, but the disparities caused by structural oppression are all too real. Black and Hispanic people are over 2 times as likely as White counterparts to live in substandard housing environments.[18] Substandard housing is living with conditions that are inadequate in terms of physical, chemical, biological, and social environment, or with inappropriate building, equipment, and amenities.[19] A person in substandard housing may experience inadequate heating or cooling (physical environment), face exposure to carbon monoxide or lead (chemical environment), have infestations of pests like rodents or cockroaches (biological environment), struggle with anxiety due local crime (social environment), have to deal with malfunctioning appliances or plumbing (building), or any combination of these.[20] All of these factors can decrease quality of life and potentially cause negative health outcomes.[21]

Housing insecurity compounds the health detriments of substandard housing, harming physical, mental, and financial health.[22] The disruption of evictions is linked to disparities in mental health, birth outcomes, and mortality.[23] Black single mothers face the highest rates of eviction in the U.S.,[24] and this disparity causes severe financial and health impacts for themselves and their children.[25] Eviction can lead to extended periods of homelessness,[26]and homelessness is correlated with extreme disparities in health and mortality.[27]

Public health and policy interventions can address disparities in housing and health,[28] but to be truly effective communities must be engaged in the changes. Addressing the “community” ring of the SEM requires collaboration with and empowerment of community members.

Community Engagement

Whether it is public health policy or the fundamental relationships of democratic governance, community engagement is critical to sustainable solutions.[29] Historically, power has been distributed with gross inequity, leading to serious social, political, and public health consequences for marginalized communities.[30] Internationally, effective community engagement is viewed as the central pillar to achieving healthy communities.[31] The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the definition “the process by which individuals and families assume responsibility for their own health and welfare and for those of the community, and develop the capacity to contribute to their and the community’s development”[32] to broadly capture the goals of community engagement. When using greater specificity, academic frameworks can help inform real-world policymakers as they strive for the ideal of authentic community engagement.

There is no single strategy for community engagement. Every community is too unique for black-and-white rules or recommendations. However, these frameworks, considerations, and guiding strategies can empower local governments to pursue community engagement with thoughtfulness and equity.

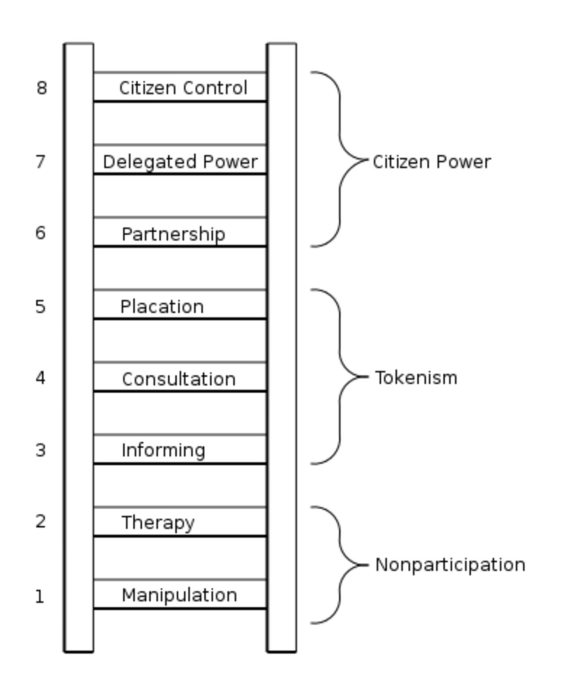

The Ladder of Citizen Participation

One of the foundational frameworks for community engagement is Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation [Figure 2].[33] Arnstein explained her ladder in terms of empowering the “have-nots” of U.S.’s communities, the people who are “excluded from the political and economic processes.”[34] Her solution to these persistent structural disparities against racial and other social identities—her “have-nots”—was to ensure that they were “deliberately included in the future” in planning, decision-making, and implementation of policies that impact them.[35] The ladder segmented eight levels of engagement that ranged from exclusionary “non-participation” to highly inclusive “citizen power.”

The first two rungs of the ladder, Manipulation and Therapy, involve exploitative practices that only use the facade of participation to either control or placate communities, not authentically involving them in political processes. The third rung, Informing, involves education of community members but does not grant them any real power. The fourth and fifth, Consultation and Placation, give community members token roles in the process in the form of providing feedback and recommendations. Again, with these two rungs communities do not have true authority, only a surface level amplification of their voices by the decision-makers with real procedural power. However, in rung six Arnstein describes the beginnings of true citizen power in Partnership, where community members are given actual authority as part of an authentically collaborative process. When the ladder reaches Delegated Power, there is a fundamental redistribution of power with true authority, over at least parts of the process, shifting from established powerholders to the former “have-nots.” Finally, in Citizen Control, community members gain full authority over the program or policy that impacts them.

Arnstein’s ladder has been incredibly influential, but it has its limitations. While the simplistic metaphor of a ladder serves as an effective tool for explaining types of community engagement, that same simplicity cannot capture the messy complexity of real, living, intersectional communities. Despite these limitations, the ladder was the seed for many other parallel frameworks, including other “ladder” models—like the public participation ladder[37] and the ladder of empowerment[38]—and a shifted metaphor of “continuum” models—like the public participation continuum.[39]

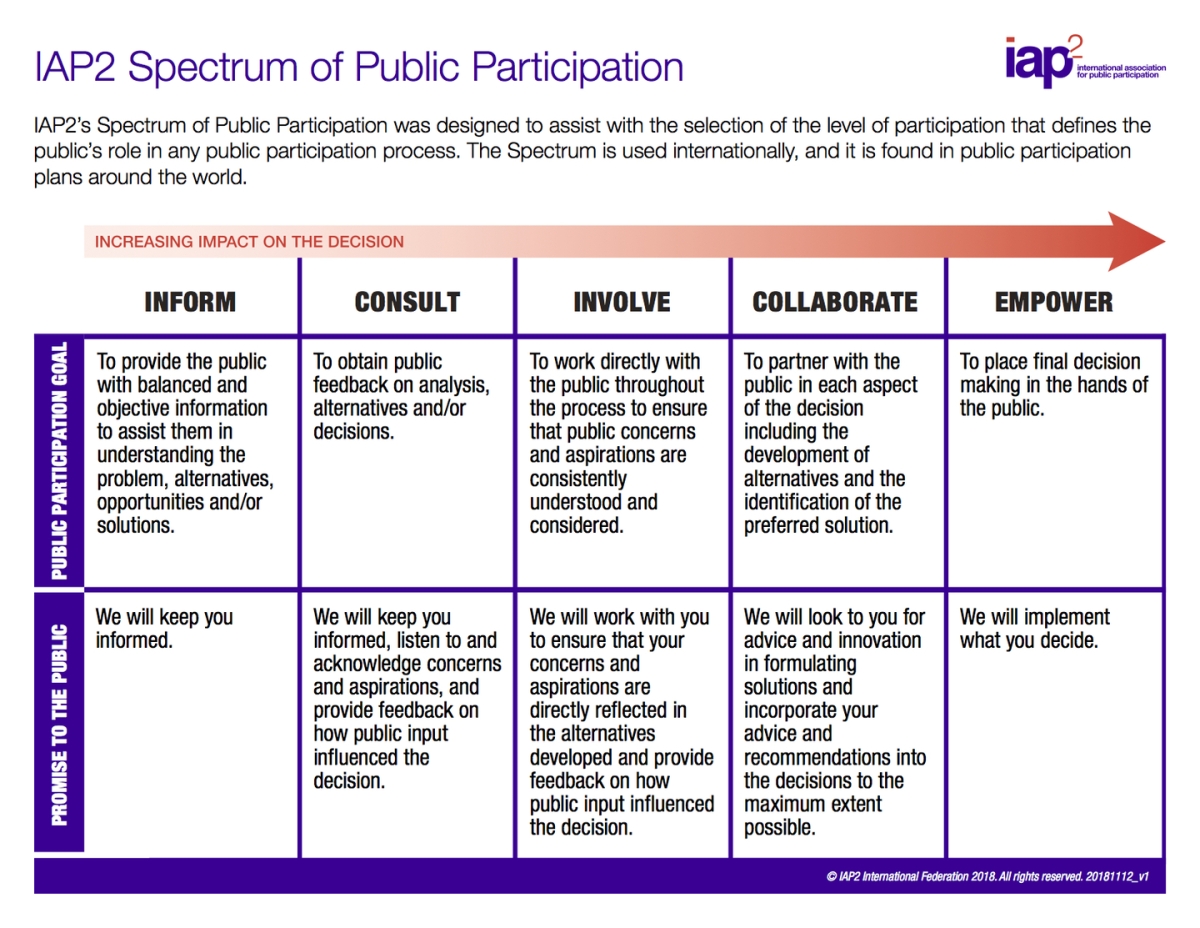

The Public Participation Spectrum

In 2004, the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) pulled key ideas from past models of community engagement to create their own utilization-focused public participation spectrum [Figure 3].[40] Ranging from least community participation on the left to most community participation on the right, this model integrates accountability—”promises” from powerholders—in addition to general “goals” of participation.

The levels of participation in the IAP2 spectrum align with Arnstein’s ladder, starting with a base assumption of minimum participation of powerholders informing community stakeholders. It was developed in accordance with the IAP2’s core ethical values[42] and as part of its mission to expand the tools and competency of engaging communities in public participation.

Benefits and Burdens

Engaging communities in health and social services requires investing time in building relationships, transparency and accountability from leaders in positions of institutional power, and intentional empowerment of community members who have been historically marginalized.[43] However, authentic community engagement can lead to numerous benefits, including improving housing management,[44] redressing health disparities,[45] promoting youth empowerment and wellbeing,[46] and alleviating burdens of crime.[47] For success, institutional values and investment of resources must align to achieve collaborative, community-led goals.[48]

True community engagement can be healthy and empowering, but it can also create burdens on vulnerable individuals.[49] For example, for people with disabilities, the burden of overreliance in a highly engaged process can lead to exhaustion and burnout.[50] This reality highlights one of the failures of both the ladder of citizen participation[51] and the spectrum of public participation[52]: In these models, maximum participation is viewed as the ideal. In reality, there needs to be a balance, with intentional empathy, communication, and flexibility built into the process to meet community members where they are over time.

Strategies for Engagement

Organizations like WHO have well-established strategies for community engagement.[53] While pursuing the authentic community engagement outlined in the Ladder and Spectrum models above [Figures 2 and 3], local governments should use intentional forethought to plan out the What, Where, Who, How, and Why for every given goal [Table 1].

|

Key Questions |

Additional Considerations |

|---|---|

|

WHAT: What type of community engagement do you need? |

|

|

What goal(s) are you trying to achieve with community engagement? |

Has this been tried before? Who has tried it? Was the community involved previously? Why or why not? |

|

What type of community engagement will achieve that goal(s)? |

Which level of engagement from the Ladder/Spectrum is appropriate? |

|

What is the timeframe/time-commitment of the community engagement? |

One-time? Until completion? Ongoing? How many hours per week/month/year? |

|

Is community engagement voluntary or mandatory? |

Will engagement be compensated? How? |

|

WHERE: Where will the engagement occur? |

|

|

Where is your community located? |

Geographic definitions? Legal/jurisdictional definitions? |

|

Where does your government fit into the community? |

How is it elected? Where is it situated? What is its authority? How is it viewed? |

|

At which level(s) of governance will community engagement occur? |

Direct/indirect authority? Boards/committees? Buildings/locations? In-person/virtual? |

|

WHO: Who will (and will not) be participating? |

|

|

What are their demographic characteristics? |

Race/ethnicity? Class? Age? Gender? Religion? Culture? Political values? Diversity/homogeneity? |

|

What are their motivations/ambitions? |

How do they define “success”? Is there agreement/disagreement in their definition(s)? |

|

What are their abilities/skills/strengths? |

Knowledge? Lived experience? Organizing? Advocacy? |

|

HOW: How will you facilitate engagement? |

|

|

What formal/informal organizations will be involved? |

Public/private? Business/non-profit? Volunteer? Advocacy? |

|

How will community members/organizations be recruited and retained? |

How will you communicate with them? How will you make the process mutually beneficial? |

|

What will their roles/decision-making power be? |

Advising? Voting? Deciding? Administering? |

|

WHY: Why do you care? Why should the community care? |

|

|

What are the planned/actual results of this community engagement? |

What are the deliverables? How will you disseminate your deliverables? |

|

What are the planned/actual benefits, burdens, and obstacles? |

Who wins? Who loses? What barriers exist for you and for the community? |

|

What lessons have you learned in the past/will you carry forward? |

What have other local governments done? What helps/hurts the process? What was/is surprising? |

These framing questions are invaluable during the planning process, and they can serve as resources to evaluate ongoing community engagement.[55] When reviewing each of these questions, it is critical to consider the distribution of power and decision making framed by the Ladder and Spectrum models above. In addition, local governments should consider which strategies for engagement match their overall engagement goals and/or project milestones. If a goal/milestone mandates community membership on a board or committee, use the SEM to determine how best to include marginalized community members without overburdening people who are already vulnerable. If a goal/milestone involves raising awareness, consider what local media, social media, and community organizations are best positioned to disseminate your message. If a goal/milestone requires long-term community interest and momentum, brainstorm what awards, recognitions, and deliverables can contribute to a reciprocal relationship between local government and community members.

Context for Reform

Open public participation defines the ideal of American democracy, but in reality the U.S. political process was built upon white supremacy to benefit white land-owning men and exclude everyone else.[56] Since the beginning of our nation, the dominant white political class has systematically excluded people of color from political and policy implementation processes.[57] This exclusion contributes to structural disparities in where people live, work, and play, creating persistent health disparities by race,[58] socioeconomic class,[59] sex and gender,[60] and other intersectional identities. International advocates demand “nothing about us without us.”[61] In political decisions that affect people with marginalized identities, policy makers and local government officials must actively incorporate the voices and wisdom of their communities in order to make lasting improvements in health, dignity, and wellbeing. Community engagement paves the way to governing ideals and flourishing communities.

Both government and private actors have made attempts to encourage community engagement in housing. These attempts vary in their tactics and sources of power. The following section will detail a number of these attempts.

Legal Context

Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty” in the 1960s demonstrated a major federal effort to remedy the nation’s affordable housing crisis. The Johnson administration recognized the necessity of community engagement for overcoming poverty, so they mandated it in political processes through requirements of “maximum feasible participation.”[62] These mandates empowered previously marginalized communities, creating new pathways for civic engagement and reform.[63]Though federal mandates of maximum feasible participation were repealed under the Reagan Administration in 1981,[64] organizations like the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are an extended legacy of the initial era.

The Obama Administration attempted to revitalize the federal mandate for community participation in 2015 through a HUD rule titled “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing” (AFFH). The AFFH’s stated purpose is “to provide program participants with an effective planning approach to aid program participants in taking meaningful actions to overcome historic patterns of segregation, promote fair housing choice, and foster inclusive communities that are free from discrimination.”[65] The AFFH also required those receiving specified HUD funds to “give the public reasonable opportunities for involvement in the development of the [Assessment of Fair Housing].”[66] Scholars indicate the AFFH’s true potential can only be realized through extensive grassroot advocacy and vigilance.[67]

Despite being finalized as recently as 2015, the AFFH has already led a tumultuous life. In 2020, the Trump administration repealed the rule,[68] but in 2021 the Biden administration indicated a desire to revive the rule.[69] Due to the uncertain nature of the AFFH, at least one state, California, has decided to adopt the rule at the state level to promote fair housing.[70] It is currently unclear whether any other states may follow suit.

Advisory Boards

Cities across the United States have created “Housing Advisory Boards” or “Resident Advisory Boards” as an attempt to increase community participation in housing discussions and decision making.[71] Advisory boards are tasked with reviewing the plans of public housing agencies and providing suggestions.[72] Public housing agencies are then required to consider the advisory board’s recommendations.[73] The public housing agency is not required to adopt all the recommendations, but they are required to submit these recommendations as an attachment to the finalized plan.[74] The public housing agency must also include a narrative describing their analysis of the recommendations and the decisions made on these recommendations.[75]

Advisory boards are supposed to be composed of community members who have an understanding of and a stake in the local housing market.[76] Ideally, the advisory board members should be representative of the community in terms of socioeconomic status and their demographic information.[77] However, many advisory boards suffer from a self-selection problem.[78] This means many advisory boards are composed of more affluent community members who have the expendable time to volunteer for the advisory board.[79] To alleviate this concern, some advisory boards have implemented quotas within their bylaws calling for a certain number of board members from varying backgrounds, like Section 8 residents and/or elderly residents.[80] Without these types of quotas, an advisory board may be representative of developers or other affluent interests, instead of your average community member.

Community Contracts

Community Benefit Agreements (CBA) are contracts between a community coalition and a developer.[81]These community coalitions may be composed of community members, local workers, faith communities, and labor unions.[82] In a typical CBA, community members agree to support the developer’s proposed project, or at least promise not to oppose the project or to invoke procedural devices or legal challenges that might delay or derail the project.[83] In return, the developer agrees to provide to the community such benefits as assurances of local jobs, affordable housing, and environmental improvements. CBAs are now commonly used nationwide to resolve disputes between developers and community members.[84]

There is debate amongst legal scholars whether CBAs are beneficial or detrimental to community members.[85]Some argue that, when properly negotiated, CBAs lower transaction costs, enhance civic participation, and protect taxpayers.[86] CBAs are meant to provide the community a voice in local development while furthering concepts of economic justice.[87] However, a key criticism focuses on whether the coalition negotiating CBAs is truly representative of the affected community.[88] In many cases, the people who negotiate CBAs are neither elected nor appointed by the community.[89] In those instances, community members have no way of holding the negotiators accountable for the conduct or outcome of the negotiations.[90] Negotiators who are not well organized, who are weak or unskilled bargainers, or who do not represent the community’s interests can dominate the negotiations unchecked.[91] However, when properly negotiated by those truly representing the community, CBAs appear to have great potential.

Some CBAs include local municipalities as a party to the contract; however, this creates added concerns about the enforceability of the contract.[92] CBAs between a developer and an entirely private coalition will follow the regular rules of contract law.[93] When a municipality joins the coalition, then the developer is afforded constitutional protections they would not otherwise have.[94] This has led some to discourage municipalities from directly participating in CBA negotiations and instead functioning as a supportive outsider.

Case Studies on Community Engagement

There are a variety of initiatives across the country being tried at the municipal level intent on increasing community participation and remedying past injustices. Cities across the country have enacted a swath of well-intended policies, some of which have achieved their goal while others have missed the mark. These policies include both top-down and bottom-up approaches. They also vary in what “Rung” on the “Ladder of Citizen Participation” (See, Figure 2) or what “Stage” of the “Public Participation Spectrum” (See, Figure 3) they fulfill. Through careful analysis important policy takeaways can be learned from each example.

Los Angeles, CA: Incentivizing Affordable Housing Developments

Summary

The city of Los Angeles is known for its disastrous unaffordable housing prices.[95] The city has taken on a variety of initiatives to address the problem from a regulatory standpoint. A significant change came through an expedited environmental review process. The city instituted the Greater Downtown Housing Incentive Ordinance,[96]which was a series of regulatory changes that were designed to increase density and reduce the administrative burden of development. The ordinance eliminated the maximum for units per lot within the relevant floor area ratio, yard requirements, parking space requirements for units affordable to those at or below 50% Area Median Income (AMI), and required percentages of private and common open space for buildings. In place of the required percentages of private to open space, a bonus system was created. It also instituted inclusive zoning requirements of 5% very low income, 10% low income, 15% moderate-income, or 20% workforce housing (150% AMI).

Also out of California were two projects that highlight an interesting strategy to overcome a lack of political will or general opposition to new housing construction. In 2001, the State of California started something called the “Jobs-Housing Balance Incentive Grant Program” (JHB Program),[97] which was a grant-giving organization that gave grants to cities that used the money on housing infrastructure and amenities.[98] The other case was of tax credits to people in the vicinity of a proposed project in exchange for not opposing the project.[99] Both of these policies are in effect paying entities that might otherwise prevent more housing development in exchange for their help/compliance in getting projects built.

Policy Takeaways

The policies initiated by the city of Los Angeles provide examples of how to incentivize the development of affordable housing. The Greater Downtown Housing Incentive Ordinance encouraged affordable housing through zoning law. Los Angeles conditioned developers’ desire for more units per building on the developers’ willingness to set aside housing for varying levels of household income. This use of zoning law represents a municipality effectively using a key power to shift incentives. The tax credits provided to developers willing to invest in “affordable rental housing for low-income Californians” is yet another example of properly incentivizing developers by meeting their interests. Los Angeles still has a long road before its housing crisis can be considered remotely “solved,”[100] but the city’s attempts at incentivizing development provides an example for other municipalities.

Chicago, IL: Addressing the Costs of Segregation

Summary

Lack of public engagement contributed to huge disparities in Chicago. The suburbs of Chicago are highly economically and racially segregated.[101] These divisions cause substantial disparities in both private and public investment across the city’s suburbs. Often predominately Black and Brown communities do not receive the same level of investment as their White counterparts. This leads to higher social spending, lower socioeconomic status, lower educational attainment, and higher homicide rates in areas with minimal investment. Because of these negative effects, Chicago is currently implementing the “Our Equitable Future” plan.[102] This plan includes actions like joining the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE), increasing affordable housing, conducting a regional assessment of fair housing, expanding homeownership, promoting economic development, investing in equitable education, and reforming the criminal justice system.

Policy Takeaways

Chicago’s “Our Equitable Future” plan is in its infancy, since it only began in 2018. There has yet to be an empirical evaluation of the plan’s impact. However, the plan’s constructors expect “billions in new tax revenue, increased safety, better health and personal safety.”[103] The plan’s constructors note “affordable housing builds strong communities” and “community organizing unlocks the talents of local residents.” This increased strength and wealth of currently untapped talent can do so much for a city.

Boston, MA: Resident Advisory Board Designed for Community Representation

Summary

Boston, MA established their Resident Advisory Board (RAB) in response to the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act of 1998.[104] The Boston RAB website includes detailed descriptions of the RAB’s bylaws[105]and history.[106] The RAB advises the Boston Housing Authority (BHA) in the development and implementation of the Housing Authority’s Annual Plan.[107] The BHA is required to consider the recommendations of the RAB in preparing the final public housing agency plan and any amendments to the same.[108] The BHA is also required to include a copy of the RAB’s recommendation and a description of the manner in which the recommendations were addressed in the public housing agency plan submitted to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).[109]

The RAB is designed to “adequately reflect and represent the residents assisted by the BHA.”[110] The RAB is meant to contain 30 members to be selected from three constituencies of the BHA: 10 from BHA’s elderly/disabled public housing developments; 10 residents from BHA’s family public housing developments; and 10 participants from BHA’s Section 8 voucher, homeownership, or moderate rehabilitation program.[111] Each of these three constituencies has distinct elections when determining the 10 representatives from their constituencies.[112] This broad approach to membership is an attempt to guarantee historically marginalized populations are able to be heard.

Policy Takeaways

The RAB in Boston, MA provides a strong model for promoting community engagement, but it is not perfect.[113] Most importantly, the Boston RAB takes steps to ensure its membership is composed of traditionally disenfranchised persons by having an expansive number of board members (30 in total) and allocating a set amount of board positions to specific demographics. With ten members from each specific demographic, no individual member is forced to speak on behalf of their entire group. Instead, each member has other representatives from their demographic present at the table. This strategic inclusion is something to be admired.

The Boston RAB advises the BHA, but it does not have final say on any specific matter. This places the Boston RAB at the “Partnership” or the “Placation” rung of the Ladder of Citizen Participation (See, Figure 2), or the “Collaborate” stage of the Public Participation Spectrum (See, Figure 3). RAB members are active participants, but there is no guarantee the RAB’s recommendations will be incorporated by the BHA. However, since the BHA is required to include the RAB’s recommendations and a description of the manner in which the recommendations were addressed in the public housing agency plan submitted to HUD, this may be considered “power… in decision making.”

Although the Boston RAB focuses on the relationship between residents and the BHA, this model of participation can be implemented in a variety of housing contexts. For example, this same model could be applied across a sector of large apartment communities in a given city. Despite the absence of a housing authority, this sector of apartment communities could still establish a representative board of community voices by using recruitment and quota methods similar to those seen in the BHA bylaws.

Irving, TX: A Housing and Human Services Board with a Self-Selection Bias

Summary

Irving is a first-ring suburb of Dallas, TX. Irving has a diverse population like Brooklyn Park. Irving’s population of 239,798 residents is broken down demographically in the following way: 21.6% White, 14.2% Black, 19.7% Asian, 42.3% Hispanic/Latino.[114] The Irving Housing Advisory Board is composed of qualified voters from Irving, TX.[115] Board membership is limited to “residents of the city who [are] eligible to vote in city elections.”[116] Board members are appointed by the city council.[117] There are no quotas or specialized incentives to encourage a diverse board.

The board assists in “the implementation and administration of all programs funded through the Community Development Block Grant, HOME Investment Partnerships Grant, and Emergency Shelter Grant programs.”[118] The Board reviews proposed policies/procedures, makes recommendations to relevant government bodies, and functions as an appeal board for city-implemented programs funded through one of the previously listed programs.[119] The board is required to report its activities to the city council as requested.[120] Any action or inaction of the board may be approved, amended, reversed, or overruled by the city council.[121]

Policy Takeaways

The Irving Housing and Human Services Board is a poor example of a citizen advisory board for two key reasons. First, since the bylaws do not specify any details about potential board members except “residents of the city who [are] eligible to vote in city elections,” the Board exhibits a self-selection problem. This means people whose voices could greatly benefit the board’s representation of the community choose not to participate, while people who may not be representative choose to participate. The self-selection problem can lead to the board’s nine positions being filled by developers and not having a single low-income resident present. This leads to the second large problem: the Irving City Council has far too much power over the board. Board members are appointed by the city council and the city council can approve, amend, reverse, or overrule any action or inaction by the board. This extensive oversight limits the potential for diverse voices to be placed on the board and raises doubts about what, if any, power the board wields. These policies mean the Irving Board is only nominally representative of the local community.

The Irving Board only reaches the “Consultation” rung of the Ladder of Citizen Participation (See, Figure 2), or the “Consult” stage of the Public Participation Spectrum (See, Figure 3). However, there is an important caveat. The Irving Board does little to address who is being “consulted.” The Board’s self-selection problem means that those most affected by affordable housing policy may not be consulted. Rather, those in positions of power, like developers or landlords, may be the only voices being heard.

Despite the Irving Housing and Human Services Board’s flaws, it has a noble aspect which should be emulated. Namely, the board functions as an appeal board for city-implemented programs funded through a list of programs. This appeal function could allow a similar board to exert power over city decisionmaking beyond simply preemptive suggestions. By allowing a citizen advisory board to review appeals, a board could voice their concerns/recommendations at several stages of the decisionmaking process.

Detroit, MI: Concerns of Government Overinvolvement through a Community Benefit Ordinance

Summary

In 2016, Detroit voters approved a “Community Benefits Ordinance” (CBO) which requires developers to proactively engage with the community to identify community benefits and address potential negative impacts of certain development projects.[122] The CBO applies when a development project: (1) is $75 million or more in value, (2) receives $1 million or more in property tax abatements, or (3) receives $1 million or more in value from city land sale or transfer.[123] When a development project triggers the CBO process, a Neighborhood Advisory Council is established, with nine representatives from the project’s impact area, to work directly with the developer and establish community benefits.[124]

Policy Takeaways

Some scholars have concerns about the effectiveness and enforceability of the CBOs developed from Detroit’s ordinance.[125] First, there is concern that developers will be less able to acquire community support for their project, when obtaining a CBA is required by local ordinance.[126] This could make it more difficult for developers to attract investors to fund the project, since developers could no longer rely on community support to ensure project approval, thereby taking away a very valuable bargaining chip that developers had relied on in the past to attract investors.[127]Additionally, by having the City of Detroit listed as a party to the CBA certain Takings Clause doctrine would apply.[128] This would further complicate the enforceability of the CBA.

CBAs are a powerful tool of community power. To be executed properly CBAs must have community actors heading the initiative. When this occurs, CBAs can reach the “Citizen Control” rung of the Ladder of Citizen Participation (See, Figure 2), or the “Empower” stage of the Public Participation Spectrum (See, Figure 3). Although well-intended the Detroit Ordinance actually reduces community power, by placing the local government at the head. The Ordinance lowers any resulting CBAs to the “Partnership” rung of the Ladder of Citizen Participation (See, Figure 2), or the “Collaborate” stage of the Public Participation Spectrum (See, Figure 3). This reduction in community also comes with a host of new challenges regarding the enforceability of these government-backed CBAs. The Detroit Ordinance showcases how well-intended policy can actually interfere with community power. The best way for a municipality to assist with CBAs is to provide legal resources for community members, not to require developers to sign CBAs.

Boulder, CO: Apply Digital Tools to Broaden Engagement

Summary

Code for America, based in San Francisco, has worked with different local governments across the country and co-designed several in-person and digital tools to increase participation and engagement for these governments.[129]Before working with Code for America, the City of Boulder applied engagement strategies including large events, small working groups, online information sharing, and feedback collection through surveys. However, there was a need to broaden the outreach toward underrepresented audiences. To achieve this goal, Code of America’s expertise partnered with the City’s Communications Department and Department of Planning, Housing and Sustainability, the Housing Boulder Process Subcommittee, and working groups composed of public interest groups in housing issues.[130] Code of America helped modify the city’s existing engagement strategies in a six-month period that improved the effectiveness of reaching out to and engaging a broader scope of community members.

Their modifications included the following: 1) The working group met community leaders and attended their meetings to build trust. Student organizations and young professional associations were connected to bridge the city with more young residents. 2) The city’s website was revamped to highlight important information about ongoing initiatives and provided visitors the opportunity to participate in an online survey regarding housing issues. Clear links were provided on the website to allow visitors to get involved, learn about the city’s housing issues, and learn about housing options. 3) Digital tools and techniques were used to make community engagement practices more approachable. For example, Textizen (created by Code of America) could create text message (SMS) surveys and analyze results, which attracted interest and connected audiences with the city’s website; Twitter was used to promote communication with residents during community meetings and events; Meerkat and Periscope allowed to live stream events and meetings and broadcast them to the public from a mobile device; Zoom allowed residents to participate in conversations remotely; SurveyGizmo conducted polls easily; CityVoice (a place-based call-in system created by Code of America) helped collect community feedback from gathering places through the telephone. 4) The community engagement was strengthened through regular actions with residents (i.e., surveys, research projects) and positive feedback loops (i.e., appreciation, information release, product presentation).[131]

Policy Takeaways

The City of Boulder’s strategy realized “involving” residents according to the Public Participation Spectrum and reached the “consultation and placation” level according to Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation by giving community members token roles in the process in the form of providing feedback and recommendations. By creating partnerships and working with community groups who were already engaged with residents, the working group could reach out to a broader scope of audiences. Comprehensive use of 21st-century techniques benefited the city to obtain wider participation in events and conversations, especially during the pandemic. This case shows an example of how to better inform community members, collect information and feedback from residents, and involve their voices in decisionmaking by comprehensively applying in-person and digital channels.

New York City, NY: Community Empowerment through NeighborhoodStat for Crime Prevention[132]

Summary

NeighborhoodStat is a major part of the New York City Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP)—a comprehensive community-based strategy to increase safety and security across 15 public housing developments in the city.[133] Developed by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (MOCJ) and partnering with the Center for Court Innovation (CCI), Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement, and Southside United—Los Sures, NeighborhoodStat employs a series of community meetings that engage residents and MAP partners in sharing data, identifying public safety priorities, and implementing solutions.[134] MOCJ and community partners collaboratively identify, hire, and train MAP engagement coordinators. Then, these engagement coordinators identify resident stakeholders, build up resident stakeholder teams, and facilitate weekly community meetings at each housing development. Through these meetings, residents are empowered to come up with action plans and vote on how to spend up to $30,000 for projects and events to increase safety and security and relative issues, based on community-based research results. Once each year, senior executives from NYC agencies and MAP residents meet in a Central NeighborhoodStat meeting to solve issues that remain unresolved locally through resident stakeholder teams.[135] Through this approach, between 2014-2019, 338 new locks and over 6,000 outdoor lights were installed in these housing developments; 954 young people were enrolled in mentoring programs; and 4,476 residents were connected to public benefits in the community.[136] In Spring 2017, 175 tasks were generated from NeighborhoodStat meetings, directed to different MAP partners, and 81% were completed by fall 2017.[137] In 2019, the resident stakeholder teams engaged 353 team members and 1,600 resident participants in the citywide participatory budgeting process,[138] who were invited to provide ideas regarding projects and/or social programming to solve a diverse set of issues that influences quality of life. Together, over 6,100 idea cards were collected in six weeks.[139]

Policy Takeaways

The NeighborhoodStat approach shows a doable community engagement model toward a collaborative effort between local government, community organizations, and residents. By including residents’ voices and empowering residents in safety-related issues, the bottom-up NeighborhoodStat stands on the “partnership” level on Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. The regular meetings held by each resident stakeholder team create an open space that allows residents to share information, express feelings, generate ideas, and discuss issues. The annual borough-wide Central NeighborhoodStat meetings hold policy decisionmakers accountable to deliver services and implement solutions. In this approach, residents—not only organizations in the community—can directly share community leadership in the power dynamics. They are no longer passively receiving information or being informed about decisions but actively engaged in the budgeting and decisionmaking process. It guarantees that practices are responsive to residents’ needs, which improves the efficiency of community resources.

The key to a successful implementation of this approach is 1) to have a city-wide consensus and commitment on utilizing community engagement and empowerment to solve community issues; 2) to identify and partner with community organizations that are involved with local residents, especially those experiencing difficulties in life, so they can build trust and connect city agencies and residents; 3) to be open to engage a wider range of stakeholders and agencies working on interrelated community issues; 4) to develop a transparent and sustainable accountability procedure that city officials and service providers will fulfill requirements from residents.

Brooklyn Center, MN: Local Example of Participatory Action Research[140]

Summary

The Brooklyn Bridge Alliance for Youth (BBAY) helped Brooklyn Center youth (81 participants) facilitate a participatory action research project that explored the central question: “What do you want to see in Brooklyn Center in 2040 that would help you reach your fullest potential, stay in Brooklyn Center and build an awesome city?” The report details the background of the project, the facilitation methods used to engage youth, the demographics of the participants, and key findings that came out of the project. The report ends with BBAY explaining how deeply the “facilitation team was struck by the clarity with which young people spoke on their vision for the community, and for their desire to develop Brooklyn Center into a city that reflects and celebrates that diversity of people who live here now.”

Policy Takeaways

This study was initiated due to efforts made by the City of Brooklyn Center to get input about the Opportunity Site that is a part of the Becoming Brooklyn Center initiative. It demonstrates the insight available from all community members, but it only represents community “Consultation” (See, Figure 2). As the researchers stated, they were “struck by the clarity with which young people spoke on their vision for the community.” This should serve as a testament to the untapped knowledge which is present in our communities. While the means that BBAY used to engage with the community are notable, it should also be mentioned that the facilitators specifically underscore how they ignored broaching questions about the consequences of development leading to gentrification and possibly displacement. This decision to not broach certain questions, raises the question of when, or if, certain topics should be avoided to facilitate discussion with citizens as well as the ethics of this avoidance.

NOAH Preservation and Community Engagement

NOAH Preservation for Housing Affordability

Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH), without a fixed definition, has been commonly recognized as existing rental properties that are currently affordable for modest-income homeowners and renters but are not subsidized by any federal program.[141] These properties tend to be Class B or Class C properties (or Class 4d in Minnesota), over 20 or even 30 years old, and with rent between $500-$1200. Preservation of NOAH has a lower cost and can extend the service life of affordable housing, thus not only solving the problem of short-term housing affordability, but also improving long-term housing stability.

For those regions and cities with the more serious housing crisis (e.g., Los Angeles, Chicago), the exploration of NOAH preservation approaches started earlier. In general, there are three types of approaches: private/for-profit effort, cross-sector collaboration (usually led by community-oriented non-governmental collaboration), and mission-oriented efforts by social-purpose real estate investment trusts (REITs). In Minnesota, mission-oriented social-purpose REITs, such as the NOAH Impact Fund, have also been established for NOAH preservation, and there is no lack of cross-sector collaborations. The Local Initiative Support Corporation (LISC) Twin Cities has led investments in NOAH preservation in multiple cities through collaboration with both nonprofits and local governments. Since 2019, several city governments have initiated policies and programs to support NOAH preservation, including tax incentive programs and below-market-rate loan programs. The latter often participates in cross-sector collaborations. In January 2020, LISC’s National Equity Fund (NEF) and LISC Twin Cities used a total of $77 million to finance Aeon’s Huntington Place in Brooklyn Park, and the City of Brooklyn Park paired $5 million. 834 units would be affordable at or below 60% AMI.[142] In general, these cross-sector collaborations have helped preserve over 1,200 NOAH units. (For a detailed literature review on NOAH preservation, please read the Appendix-NOAH Preservation:Significance, Challenges, and Practices.)

The Lack of Community Engagement in NOAH Preservation

Community engagement is critical for NOAH preservation, as well as other affordable housing development practices. A high-level community engagement with residents is assumed to allow preservation practices to meet the needs of communities. Cross-sector collaboration with mission-oriented social-purpose REITs and nonprofit organizations in NOAH preservation has addressed community engagement to some extent. With expertise, opinions, and contributions from public and private organizations in the community, NOAH preservation practices could target the most-needed locations, properties, and populations. However, even this strategy lacks engagement with citizens/residents as a valued part in the Ladder and Spectrum models [Figures 2 and 3].

By involving residents before, during, and after rehabilitation projects of NOAH properties, residents should be informed about the rehabilitation process and consulted if any concerns arise with newly preserved affordable properties. Unfortunately, there are no examples of such practices across the country. Public-private partnerships usually end after rehabilitation is completed, and there is a lack of continuous community engagement in housing management. In future cross-sector collaboration, local governments may consider reserving part of the NOAH preservation investment for community engagement, including developing or enhancing an advisory board consisting of residents and other community stakeholders, and coming up with an appropriate Community Benefit Agreement (CBA) with it.

Conclusion

Community engagement is a key tool for promoting health and stability. With an understanding of social determinants of health and the application of engagement frameworks, local governments can build flourishing futures through the partnership and empowerment of community engagement. Brooklyn Park is a diverse and growing city, but it has housing disparities that impact community health. The local government could learn from different levels of community engagement strategies applied by other local governments in the case studies. Indeed, not many practices have reached high levels of community engagement in housing issues as defined by Arnstein in the Ladder of Citizen Participation Theory. Consulting with and informing residents of policies, developments, and actions related to housing issues increases transparency of practices and values residents’ voices, but it is not enough to mobilize and empower residents in decisionmaking. Residents’ knowledge, experiences, opinions, needs, and passion should be utilized through a more comprehensive design of the community engagement plan, especially when it comes to issues related to their safety and quality of living. It is no doubt that it requires a deliberate design, sustainable funding, time and energy, and city-wide collaborative commitment to develop and maintain a high level of community engagement. However, there is a trend to collaborate with residents and integrate top-down and bottom-up solutions in housing issues. The NeighborhoodStat program initiated by New York City serves as an example for the City of Brooklyn Park, which is a collaborative effort between local government, community organizations, and residents. Most importantly, residents are not only informed or consulted regarding housing issues, they are empowered in needs assessment and the budgeting process. In all, authentic community engagement has the potential to create equitable and sustainable solutions to housing issues for the future. Organizing advisory boards, holding stakeholder teams accountable, applying diverse in-person and online techniques, and properly establishing Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) are methods to fulfill residents’ participation, while more creative solutions are waiting to be identified.

Methodology

Introduction

CURA advocates for the necessity of community-engaged research—centering the knowledge and inclusion of community members throughout the research process. This research model inverts the power dynamics commonly seen in community-based research, where an academic enters a space with a predetermined focus and questions, extracts data from the community, analyzes data without the inclusion of community voices, and disseminates findings within their peer communities. Rather than the community being a means to a “scholarly end” this model asserts that collaboration with community members produces research that is not only robust, but also bolsters trust, usage, and accessibility for practitioners and policymakers. The Brooklyn Park Housing Project and its Advisory Council (a diverse collection of community stakeholders) upheld this CURA research standard.

Research Design

This is a mixed method research project. By using both qualitative and quantitative research approaches, the intent is to offer a more comprehensive examination of housing experiences in the city’s large apartment communities—for its renters and property management team members. Qualitative data was collected through all project data sources: an intake form, interview and focus group questions, as well as a project survey. The project’s quantitative data was generated from the intake form and survey. The CURA research team was shifting to project outreach as the State of Emergency mandate was going into effect in Minnesota in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following an initial pause as the world attempted to make sense of the virus and its ramifications, the University of Minnesota system and CURA research team had to figure out what community engagement research could look like within this context. This is work that is regularly performed face-to-face, predicated upon the importance of physical interactions, which help to build comfort and rapport between researchers and participants. In-person engagement also supports a researcher’s ability to collect pertinent information communicated through an individual’s body language and gestures as well as read those cues to further probe in their interview questions. In response to the pandemic, the large majority of project outreach and all of data collection took place virtually. Advisory Council members’ networks, city staff, and community organizations remained essential resources to help spread the word about the project, but a central approach, the ability to introduce the project and answer individual’s questions through face-to-face engagement was lost.

Project Participants

At the project’s outset the intent was to obtain participants from the eight largest apartment communities in the city. These communities were also the city’s highest and lowest eviction filers. Along with a desire to better understand the experiences of those who live and/or work in the city’s largest apartment communities, their eviction status (highest and lowest in the city) also allowed for an opportunity to see if there was any correlation between their status and experiences regarding housing quality, relations amongst management and tenants, and safety/security concerns. The CURA research team was contracted to engage with 40 participants—28 residents and 12 property management team members. Participating residents had to be 18 years of age or older. Participation amongst property management team members was open to all staff members on site who interfaced regularly with residents. This included those who worked in an apartment community’s main office (i.e., leasing agents) and those who worked on its grounds (i.e., maintenance staff).

However, following a low response rate amongst these eight apartment communities, particularly amongst property management team members,[143] it was determined to expand the participant pool to include the largest 25 apartment communities in the city. Solicitation to residents remained the same—flyering within apartment communities, utilizing the social media platforms of area community organizations and groups, the personal/professional networks of Advisory Council members, and outreach by Brooklyn Park city staff. The latter case included engagement efforts by the city’s Communication Department, Community Engagement Team staff, and flyering within municipal buildings. With the expanded participant pool, outreach strategies to property management team members became more centralized and strategic. With communications drafted by the CURA research team, engagement with property management teams was explicitly overseen by Brooklyn Park city staff who had strong professional relations with city property managers. City personnel directly funneled individuals who agreed to participate in the project to the CURA team member leading data collection. Property management team members chose the day and time for their participation and CURA research team members made themselves available. However, even with this very hands-on approach, there were still many “no shows,” frequent rescheduling, and repeated solicitation by city staff to obtain additional property management team members to secure the targeted number. The final collection of residents and property management team members who participated in the project was an extremely engaged group. However, assembling the participant pool—specifically the property management team members—became an unexpected process.[144]

Data Collection

This process was completed by CURA research team members. Data collection occurred virtually, in response to the pandemic. The large majority of the data was collected via the Zoom platform. However, for some participants internet access was less accessible or navigating the technology was cumbersome. For those who preferred to connect over the phone (all interviews and focus groups were recorded) researchers switched to that medium. It was important to meet project participants where they were. We did not want the pandemic, or the circumstances it created (virtual engagement), to interfere with an individual’s ability to participate in this community-engaged project. Per participant, data collection consisted of four touchpoints—an intake form, interview questions, focus group questions, and a survey. Each touchpoint allowed for the collection of a different type of data that related to the project’s foundational premise—communication/relations amongst tenants and management, safety/security, and awareness of rights and responsibilities for the two participant pools. Ultimately, the 40 participants resulted in 160 unique data sources that allowed the CURA research team to present a comprehensive analysis of housing experiences in the city’s larger apartment communities.

Data Analysis