Introduction

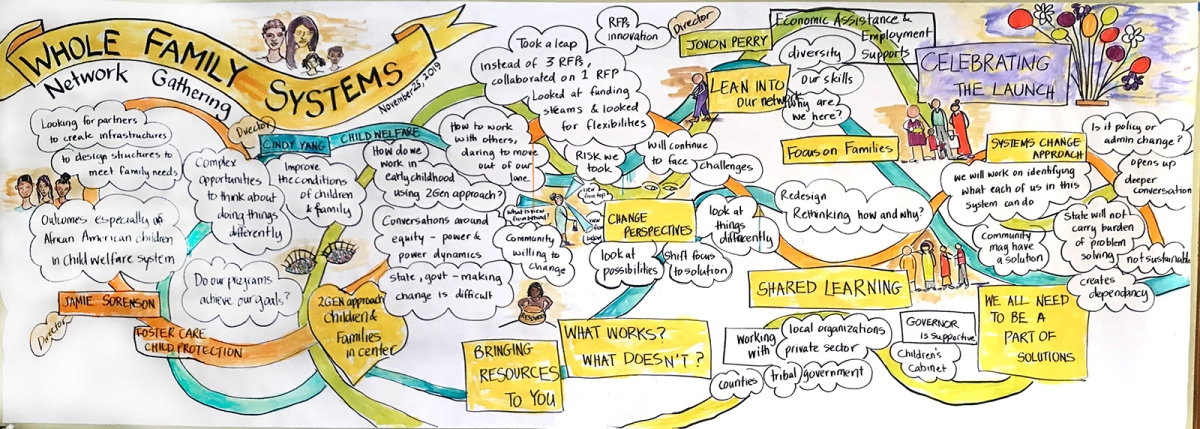

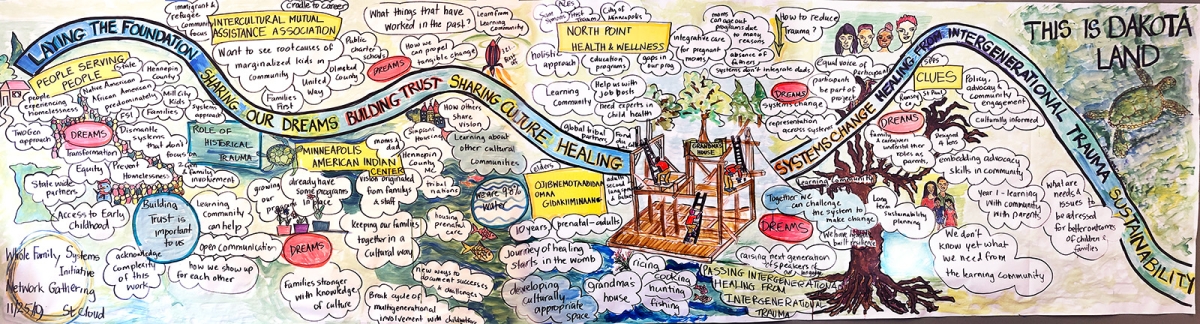

Sitting around six tables in a bright room, about forty-five civil servants from the Minnesota’s Department of Human Services joined a day-long planning session of a new policy initiative that aims at advancing two-generation approaches that improve outcomes for children and parents altogether — the Minnesota 2-Generation Policy Network. Some of the participants were apprehensive as they often got many emails and invitations to events, and they did not know what to expect. Others were cautiously optimistic as they identified with leaders’ intentions to work more authentically with organizations serving Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) over the next five years, which was mentioned in the invitation for the day. As people gathered background documents, got coffee, and got to their seats around the tables, three directors stepped to the front of the room and started their introductions.

Those three leaders, one African American woman who leads the Economic Assistance and Employment Support division, one Asian woman who directs the Child Care Service division, and one white man who leads the Child Safety and Permanency Division, came together to share a powerful message with the group: the status quo does not work, and we have to reform our public bureaucracies to make our system work for BIPOC communities. They recognized that the current human service system is highly fragmented, and it fails to provide system-level support to families in need, especially those that are in historically socioeconomically disadvantaged and marginalized communities. The current system also builds on the false assumption that the state knows what to do for BIPOC communities and they can simply contract out services to nonprofits and direct them to solve the problem. Yes, funding disparity is a key factor in driving these inequities. However, they also recognized that this problem is deeper than a redirection of governmental resources and it requires a system change in the government and an authentic partnership with nonprofits serving BIPOC communities.

“How can we each connect to that local knowledge? How do we engage families more effectively in ways they want to be engaged? How do we put equity into action and tear down institutional racism? How do we use this power that we now hold to effect change?” The three directors pose these provocative and deep questions to their co-workers in the Department of Human Services. Answering these questions requires a different way of engaging, communicating, and leading than what is traditionally done. Most importantly, they have to find ways to rebuild trust with nonprofits serving BIPOC communities and bring them along in this public management reform. Public bureaucracies alone cannot solve this problem. The three directors are excited to announce that they have blended three distinct sources of public funding to establish a “co-creative process that will uncover and address the systematic influences of racial, geographic and economic inequalities.”

Project Background

While Minnesota is considered one of the best states in terms of its high life quality, active civic participation, and vibrant economy, racial disparities between whites and other people of color in almost all indicators of individuals and community well-being are large and persistent. In other words, if you are white, you are likely to have great life quality in Minnesota. However, if you are black or brown, you are likely to suffer. Dr. Samuel Myers Jr. terms it the Minnesota Paradox.[1] The murder of George Floyd certainly pushed Minnesota to the center of national attention, but these racial disparities have existed for decades. In child welfare where the state has the authority to remove children from their parents and terminate parental rights, the over-representation of Black and American Indian children is well documented,[2] and racial biases exist at each decision point in the service continuum.[3] In early childhood education, in almost every measure of service and attainment, from diagnosis of developmental and behavioral conditions to kindergarten readiness, there are significant racial disparities.[4]

Recognizing these racial inequities in human services, the state government and the Department of Human Services have strategically hired more racially diverse program managers and promoted people of color into positions of authority. Moreover, they realized that to systematically address existing racial inequities in health and human services, community-based organizations serving BIPOC organizations have to be at the center stage as they have deep knowledge and connections with residents in those communities. The Minnesota 2-Generation Policy Network is a result of such a vision. In early 2018, three DHS Directors began planning for a larger collaborative initiative. Their first action step was to commit to blending three distinct sources of public funding: federal funds from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) targeted for innovation and quality enhancement; and state funds earmarked for efforts to reduce racial disparities in child welfare programs. In the end, seven BIPOC nonprofits and one governmental agency received five-year grants as part of the overall $22.5 million initiative.[5]

Taking advantage of the unique timing of the Minnesota 2-Generation Policy Network and the facilitator role played by the Future Service Institute at the University of Minnesota, we conducted 18 interviews and a survey of 64 applicant organizations between October 2019 and March 2020 with public managers and grantees and drew information from detailed field notes (representing more than 350 hours of learning sessions and meetings) to track the trust-building activities and outcomes in the process of forming and running this policy network.

Key Findings and Take-aways

Finding #1: Trust-building with BIPOC-serving community-based organizations is slow, hard, yet critical work.

“It’s our job to keep showing up at the table and saying, we're here to listen and we'd like to hear from you. If they say, we don't want to talk to you. Okay. But we must continue…We don't get to just turn away.”

— Niaya, government leader

“Reverberations from previous relationships [grantees had with the state] also play out. We were working with sites and saying we want something different. And they don’t really believe it. I don’t blame them. They’ve had relationships with the state before that are very structured, very constrained, and compliance-driven. While we are saying we want to try and do something different, breaking them out of the habits of interaction with the state is challenging. And sometimes we aren’t always able to carry through on wanting to be flexible and adaptable. And collaboration suffers because of that.”

— Juliette, government leader

“Individuals may desire change, but they are part of a larger structure and system and are trying to fight its inertia.”

— Jenny, nonprofit manager

Because of existing public management practices in the contracting relationship, trust between the government and BIPOC-serving community-based organizations is often absent at the beginning of collaboration.[6] Even with this long-term funding commitment and network building, community-based organizations expressed their doubts about the true intention and commitment of the government. While they appreciate the fact that three top leaders in the DHS came together for this very innovative initiative, they understand that the bureaucracy and government institutions as a whole may still marginalize them and present various obstacles. The delay in the release of the request for proposals is one such example. Existing legacy public practices and administrative rules strain the building of trust with community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities and it takes time and consistent actions from the government to rebuild trust.

Government leaders also recognize that they cannot undo all the historical harm to these organizations on their own and it is expected that these grantees came to this partnership with a sense of reservations and distrust. They have to consistently “walk the talk” to build trust with these community-based organizations. While this trust-building process is slow and hard, it has to be initiated and sustained by genuine governmental actions. Government agencies have to also begin to trust community-based organizations first and design funding mechanisms that facilitate learning and innovation, instead of the traditional funding mechanisms through strict contract conditions under which the government controls the actions of community-based organizations and merely treats them as the tool of government.

Finding #2: Creating synergies inside the government is the precondition of building trust with BIPOC-serving community-based organizations.

“We have not asked people for permission to put this funding together. We did it. And there are bodies that I still need to report to that are probably not going to be happy about it. But we did it because we felt we had sound justification….We did it because we need to try some different things. It wasn't anything about this agency that brought us together. It was us.”

— Jerry, government leader

“We talk about collaboration, but I don’t think it is always understood. Some people [who work for DHS] want to know exactly what’s expected of them at any given time. And collaboration requires adaptability and big-picture thinking. And that’s not necessarily the strong suite of state government.”

— Juliette, government leader

“I learned…there are three separate very large governmental agencies that are really actively putting their money where their mouth is and coming together as a group to offer opportunities. That was surprising to me.”

— Tom, nonprofit leader

While trust-building with community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities is challenging, synergies inside the government create the precondition for the trust-building loop to start.[7] According to our interviews and field observations, they are mainly due to two reasons. First, throughout this particular public management reform process, directors and project leaders repeatedly noted they were pushing against rigid administrative structures, an apparatus that was larger than any of their span of control. Although Directors were committed to this vision, staff working under them hesitated to deviate from conventional routines, grapple with ambiguity, and act with determination. Each step in the process to establish this collaborative governance initiative required persistent, and what often felt like courageous actions, both from those with formal authority and those who worked for them. Without a high level of trust and synergy among these directors and their staff members, these reforms would die off in the everyday routine decisions of scheduling meetings, inviting attendees, and meeting various demands from the legislature, coworkers and the public. These activities are often embedded in existing public management practices, and they consume energy and attention from the bureaucracy. With a high level of internal trust, these routine decisions and practices are transformed into opportunities for changing and creating new structures.

From the perspective of community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities, they judge the state government not only by their words and the grant announcement. More importantly, they also assess the trustworthiness of the government from their everyday experiences in meetings, webinars, and email exchanges with government employees. Without a strong synergy inside the government, their daily interactions with the government would not be consistent. This is particularly challenging when the initial level of trust is low and those community-based organizations are searching for ways to confirm their expectations based on their past experiences. In our case, the grantees were impressed when they saw three high-level state government leaders come together and put their money where their mouth is. This played a key role in activating the trust-building loop.

Finding #3: When the stock of institutional trust is low or missing, interpersonal trust is key to starting the trust-building loop.

“Even if grantees are disappointed that we don't go live [at the original date], we are building a relationship, a trusting relationship where we are being transparent. We say ‘here's what we're trying to do, we don't know if it's going to be perfect this time around, but we're doing our best.’ We ask them, ‘tell us how we can do better. Tell us what you need. That really is the key to trusting relationships, that you're open. It's not that everything goes great. It's that you're honest about what's happening…. That’s the kind of relationship infrastructure that we need to be successful in certain communities that don't trust the Department of Human Services.”

— Niaya, government leader

“The flexibility...shows me that the state is really invested in this, that they're really listening, and that they want to try something that hasn't been tried before…It is evident when you interact with them. And when you go to the next meeting, you will see that as well…. It's just so blatantly obvious because of the way that they act."

— Mike, nonprofit leader

“I saw people in the state are coming together and working to help make this place a better place…. They are good people. They want to see Minnesota and its citizens and constituents prosper and I think that was the biggest takeaway.”

— Daniel, nonprofit leader

Ultimately, organizations do not interact with each other, but people do. Community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities judge and assess the trustworthiness of the government by their interactions with people inside the government. Each interaction sends a signal to them about the intention of the government. Therefore, trust in government as an institution starts with interpersonal trust-building with government leaders and employees. As individuals, nonprofit managers from these community-based organizations do not expect perfection from their government counterparts. Instead, they expect genuine curiosity, openness, flexibility, and honesty. Even with the delay in the release of the request for proposals, trust built as state government leaders genuinely communicated to their partners regarding why that was happening and what can be done. According to our survey and interviews, leaders from these community-based organization grantees appreciated the most their interactions with state government leaders and employees.

State government leaders recognize that they need to keep showing up in meetings and that talking to their community partners is critical to the success of this collaboration. The relationship infrastructure built through these daily personal interactions is as important as those funding and institutional infrastructures. It is the combination of the funding commitment, a strong synergy inside the government, and trust-building at the interpersonal level that activates and sustains the trust-building process.

Policy Recommendations

To implement any meaningful public management reform to address racial inequities in public service provision, the government must regain trust from community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities. The legacy of existing public management practices has systematically marginalized community-based organizations and created distrust in the contracting and grant-making processes. Through studying the early stage of a system change initiative involving government agencies and community-based organizations, we find that the government’s intentional tactics both inside the bureaucracy and with community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities allowed them to create new collaborative infrastructures that both changed organizational routines and built power to address racial inequities in the existing human service system. Based on these important findings, we offer three policy recommendations from our interviews and research.

Policy Recommendation #1: Designing more flexible, long-term, and interagency funding mechanisms that emphasize learning and trust-building.

One of the important lessons from our research and interviews with government and nonprofit leaders is that the traditional way of government working with community-based organizations is no longer effective. Funding is too fragmented for any system change and the advantages of community-based organizations are minimized through rigid and control-based contracting arrangements. To facilitate system change, it is important to design initiatives that meet the boundaries of the problem, instead of the administrative boundaries of specific government agencies. In addition, to solve complex social problems, no agency holds the complete answer, including the government and community-based organizations. Therefore, it is important to create an environment where organizations are comfortable innovating and making mistakes. How to design such funding mechanisms that prioritize system change, learning and trust-building is critical as the government renews its relationship with community-based organizations serving BIPOC communities.

Policy Recommendation #2: Increasing the representation of BIPOC leaders in government and community-based organizations.

As we have illustrated in the background of our study, the Minnesota 2-Generation Policy Network was initiated and activated by BIPOC government leaders inside the DHS. It is their background and lived experiences that made them realize where the problem lies and what the solution looks like. Similarly, in our sample, the leaders and top managers of the community-based organization grantees in the network are all from BIPOC communities. However, compared to the overall landscape of state government and nonprofit leader profiles, the case of the Minnesota 2-Generation Policy is an exception. The government and nonprofit workforce, especially for those top management and leadership positions, are white-dominant. Even with these similar backgrounds in government and these community-based organizations, trust-building is very challenging. The challenges for system change are likely to be greater if it is initiated by white managers only. Increasing the representation of BIPOC leaders in government and community-based organizations is critical as we find ways to bring system change to address systematic racial inequities.

Policy Recommendation #3: Creating opportunities for government leaders to interact and build authentic relationships with nonprofit leaders from BIPOC-serving community-based organizations.

As we have illustrated in our findings, organizations do not trust each other — only people do. While leaders from the government and community-based organizations should always recognize the institutional barriers they face in addressing racial inequities, their efforts should not only focus on policies and institutions. For those efforts to be successful, they have to be able to build sufficient interpersonal trust to activate the trust-building loop, so all partners are brought along. This is particularly challenging because of the COVID-19 pandemic as things can be done more efficiently online. Sometimes, people do not even need to meet anybody in the government to get certain things done. This may be effective for certain tasks that have clear boundaries. However, based on our interviews and research, interpersonal interactions and relationship building are key to the activation and advancement of system change efforts for which uncertainties are high and no one actor gets the complete answer. Community forums and conversations are great opportunities for government and nonprofit leaders to meet each other. As what has been done by the Future Services Institute, universities and research centers may also be important intermediaries to put together such conversations.

Endnotes, Funders & Author Bio

Endnotes

[1] Briefing: "The Minnesota Paradox" and what else you need to know today

The New York Times, June 1, 2020

[2] Children’s Bureau. (2016). “Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. Child Welfare Information Gateway.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

[3] Putnam-Hornstein, E., Needell, B., King, B., & Johnson-Motoyama, M. (2013). Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 33–46.

[4] Reardon, S., & Portilla, X. (2016). “Recent Trends in Income, Racial and Ethnic School Readiness Gaps at Kindergarten Entry,” American Education Research Association Open 2(3).

[5] Sandfort, J.R, Sarode, T, & Hendriks, H. (February 2020). “Expanding Innovations that Support Whole Families: State-Level Developments in Minnesota During 2018-2019,” Minneapolis: Future Services Institute, University of Minnesota.

[6] Cheng, Y. D., & Sandfort, J. (2021). Administrative Reform to Overcome Institutional Racism: Exploring Government’s Trust Building Tactics to Renew Relationships with Community-based Organizations. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/223220

[7] Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5-31.

Project Funders & Supporters

Center for Urban and Regional Affairs Faculty Interactive Research Program

Participants of the Minnesota 2-Generation Policy Network

Author Biography

Yuan (Daniel) Cheng is an Associate Professor, Chair of the Leadership and Management area, and the Director of Graduate Studies for the Certificate in Nonprofit Management at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs. Professor Cheng also serves as a McKnight Presidential Fellow. Dr. Cheng's research is focused on a range of theoretical and managerial questions lying at the nexus of governance, government-nonprofit relationships, co-production, and the distributional and performance implications of cross-sector collaboration. In close collaboration with governmental and community organizations, Dr. Cheng is currently embarking on new research directions to better understand the implementation of evidence-based practices in government, the policy impacts of academic research, and how to design more inclusive public sector grant-making programs.